Anti-Black police violence rooted in the slave trade: Harvard researcher

Published: February 9, 2021

Police violence against Black people can be traced to the brutal slave trade led by Europe’s great powers centuries ago, says award-winning author and historian Professor Vincent Brown of Harvard University.

Brown made the remarks during the recent A&S Decanal Lecture put on by the University of Toronto’s Faculty of Arts & Science, an inaugural community event to celebrate Black History Month 2021.

The title of Brown’s talk, given over Zoom, was “The Coromantee War: Charting the Course of an Atlantic Slave Revolt.”

“One of the things this history reminds me of is that racism is not just about exclusion or impoverishment; it's also about anti-Black militarism as a cultural logic that grows out of slavery,” Brown said.

“If one sees slavery itself as a state of war, it becomes easy to see the execution and the continuity of that kind of anti-Black militarism today.”

While disproportionate police brutality against Black women and men in the United States also has roots in court rulings and gun culture, there is a striking similarity with other former slave societies, Brown added.

“Throughout the Americas, in places like Brazil or Jamaica, for example, one sees that same kind of anti-Black militarism showing up in police violence, even when the police are Black,” he told attendees.

“The violence of slavery has established a kind of continuous logic that I think we're still struggling with today.”

To underscore the point, Brown drew on his groundbreaking scholarship about the Jamaican Coromantee War and his new book, Tacky’s Revolt: The Story of an Atlantic Slave War.

He noted that the early movement against the slave trade was not so much about morality as it was about protecting white societies against ever-growing numbers of militant African warriors fighting back against their capture and enslavement. The fear of Black slave revolts was so deeply rooted in events like the Coromantee War, he said, that whites in the antebellum U.S. of the 1800s often referred to rebellious Black slaves as “Tackies,” after the name of the leader of the Jamaican conflict.

The ripple effect this fear created is often overlooked because of a lack of appreciation of the significance of the Jamaican conflict and its impact on the worldwide Seven Years’ War between France and Britain, which also influenced Spain, Brown said.

“These clashes amounted to a borderless slave war – a war to enslave, a war to expand slavery and a war against slaves.”

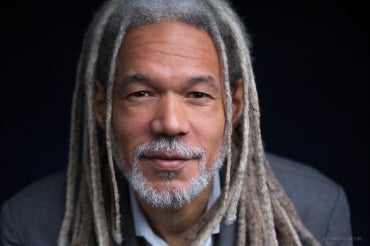

Clockwise from top left: Malaika Eyoh, Vincent Brown, Melanie Woodin and Melanie Newton.

Tacky’s revolt was one of the hardest fought battles of the Seven Years’ War. It also helped shape the British Empire’s policy toward its colonies in the Americas, with Jamaica being the richest and most profitable.

“It offered a rationale for the reform of colonial slavery,” Brown said. “Fearing further rebellion, concerned Britons put forth pragmatic plans for enhancing the security of the colonies by limiting the dependence on the slave trade.”

Tacky’s revolt encourages a fresh perspective on the political landscape of the period and the distortions that arose from the fact that slaveholders themselves wrote the first draft of the history that dominated the narrative for centuries to come, according to Brown.

“The relative obscurity of these events is also due to the reluctance to acknowledge slavery as an act of war,” said Brown, adding that the social antagonisms established by slavery persist to this day as the descendants of slaves fight for the space to develop their own notions of belonging, status and fairness.

“Few things terrify the wealthy and powerful more than the prospect of losses to the poor and the weak, which would signify dishonour and a world turned upside down.”

In her introductory remarks, Melanie Woodin, dean of the Faculty of Arts & Science, noted the inaugural lecture had attracted nearly 1,200 online registrants.

She said the strong response illustrated that the pandemic had not only created challenges, but had also presented opportunities to reaffirm U of T’s core values – even as it forces events such as the lecture to be held virtually.

“By promoting inclusive excellence with important events such as this one, and through many other ways, we can provide an enriched environment for all our faculty, staff, students and alumni to better reflect not only on the lived experiences of our community, but also on this wonderful multicultural city that is our home.”