Bad genes aren’t always bad news say U of T researchers

Published: November 4, 2016

We usually think of mutations as errors in our genes that will make us sick. But not all errors are bad, and some can even cancel out or suppress the fallout of those mutations known to cause disease. While little has been known about this process – called genetic suppression – that will soon change as University of Toronto researchers uncover the general rules behind it.

Teams led by Professors Brenda Andrews, Charles Boone and Frederick Roth of the Donnelly Centre and the department of molecular genetics, in collaboration with Chad Myers of the University of Minnesota Twin Cities, have compiled the first comprehensive set of suppressive mutations in a cell, as reported in the latest issue of Science. The four researchers are members of the genetic networks program of the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research. Their findings could help explain how suppressive mutations combine with disease-causing mutations to soften the blow or even prevent disease.

This curious bit of biology has only come to light as more healthy people have had their genomes sequenced. Among them are a few extremely lucky folks who remain healthy despite carrying catastrophic mutations that cause debilitating disorders, such as Cystic Fibrosis or Fanconi anemia.

How could this be?

“We don’t really understand why some people with damaging mutations get the disease and some don’t. Some of this could be due to environment, but a lot of could be due to the presence of other mutations that are suppressing the effects of the first mutation,” said Roth, who is also a senior scientist at Sinai Health System’s Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute.

Imagine being stuck in a room with a broken thermostat and it’s getting too hot. To cool down, you could fix the thermostat – or you could just break a window. Genetic suppression essentially “breaks the window” to keep cells healthy despite damaging mutations. And it opens a new way of understanding, and maybe even treating, genetic disorders.

“If we know the genes in which these suppressive mutations occur, then we can understand how they relate to the disease-causing genes and that may guide future drug development,” said Jolanda van Leeuwen, a postdoctoral fellow in the Boone lab and one of the scientists who spearheaded the work.

But finding these mutations is not easy; it’s a proverbial needle in the haystack. A suppressive mutation could, in theory, be any one of the hundreds of thousands of misspellings in the DNA, scattered across the 20,000 human genes, which make every genome unique. To test them all would be impractical.

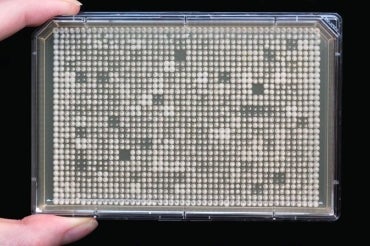

“A study like this has never been done on a global scale. And since it is not possible to do these experiments in humans, we used yeast as a model organism, in which we can know exactly how mutations affect the cell’s health,” said Van Leeuwen. With only 6,000 genes, yeast cells are a simpler version of our own, yet the same basic rules of genetics apply to both. Also, it’s relatively easy to remove any gene from yeast cells in order to study the most severe case of a mutation, where the gene function is completely gone.

The teams took a two-pronged approach. On the one hand, they analyzed all published data on known suppressive relationships between yeast genes. While informative, these results were inevitably skewed towards the most popular genes – the ones that scientists have already studied in detail. Which is why Van Leeuwen and colleagues also carried out an unbiased analysis by measuring how well the cells grew when they carried a damaging mutation on its own, or in combination with another mutation. Because harmful mutations slow down cell growth, any improvement in growth rate was thanks to the suppressive mutation in a second gene. These experiments revealed hundreds of suppressor mutations for the known damaging mutations.

Importantly, regardless of the approach, the data point to the same conclusion. To find suppressor genes, we often don’t need to look far from the genes with damaging mutations. These genes tend to have similar roles in the cell – either because their protein products are physically located in the same place, or because they work in the same molecular pathway.

“We’ve uncovered fundamental principles of genetic suppression and show that damaging mutations and their suppressors are generally found in genes that are functionally related. Instead of looking for a needle in the haystack, we can now narrow down our focus when searching for suppressors of genetic disorders in humans. We’ve gone from a search area spanning 20,000 genes to hundreds, or even dozens. That’s a big step forward,” said Boone.