Can epileptic seizures be prevented or predicted?

Published: March 28, 2014

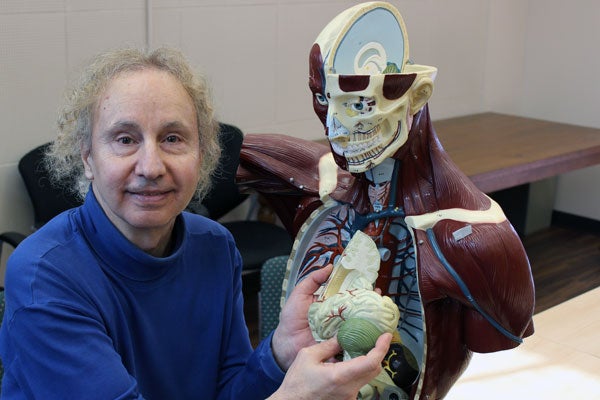

In honour of Epilepsy Awareness Month, writer Erin Vollick sat down with a leading neurological researcher at the University of Toronto, Berj L. Bardakjian.

A biomedical engineering professor at the Institute of Biomaterials & Biomedical Engineering (IBBME) and the Edward S. Rogers Sr. Department of Electrical & Computer Engineering (ECE), Bardakjian works with a team of neurological specialists to classify different brain states using recordings of its electrical rhythms, and from there, to pinpoint seizure zones in the epileptic brain – research that could reduce the amount of tissue cut during corrective surgical procedures, as well as lead to better surgical outcomes.

What is epilepsy?

Contrary to what most people imagine, epilepsy is not considered a disease, but a disorder characterized by changes in the brain that lead to seizures. But epilepsy actually covers a wide range of disorders. There is not just one type of epilepsy, but many.

Our present theory is that seizures are caused when the brain is in a state of hyper-excitability. I think of the brain as a symphony. The electrical activity in the brain is polyrhythmic, as there are many interacting rhythms, and none of them are “regular”. But with an epileptic seizure, suddenly, all the cells in the brain start synchronizing together and they enter a singular, regular rhythm, which means that all the other normal functions of the brain are not occurring.

What are some of the historical associations surrounding epilepsy?

Epilepsy used to imply “possession.” Historically, people who suffered epileptic seizures were thought to be possessed by the devil, or were entering mythical or mystical states. Personally, I wonder about many of our geniuses – Napoleon Bonaparte, Beethoven, and Van Gogh, for instance, all had epilepsy. Was their genius related to their epilepsy? Is hyper-excitability what gave us Beethoven’s 9th symphony?

What causes hyper-excitability?

Hyper-excitability occurs due to possible chemical environment changes in the brain, at times even visual changes. A few years ago, for instance, people in Japan who were watching TV were getting seizures from the flickering lights in their television programs.

How is epilepsy managed?

There are three main courses of treatment. Children who have epilepsy can be put on a “ketogenic diet” – it’s a horrible diet, very high in fat, but it can help control the seizures.

Drugs are the next step, and these drugs are designed to reduce the excitation of the brain that leads to this synchronous brain activity and seizures.

Drugs don’t work for some people, so surgery is an option. Surgeons will try to cut out that part of the brain that is the focal point of the seizures. But there are some areas of the brain that can’t be cut, such as those vital cognition areas. Also, you can only perform surgery if the epilepsy is “focal” to one region, and not “generalized” in multiple sites of the brain.

What kind of research is your team conducting?

The big buzz word right now is ‘Deep Brain Stimulation’. We’re trying to create implantable devices that can predict seizures and stimulate the brain in such a way as to prevent seizures. Via electrodes, we want to input into the brain high complexity electrical signals – like a symphony – that would mimic the rhythmic signals that normal, functioning brains produce. The simulator we’re working on is a model of the electrical rhythmic activities of the functioning brain.

This kind of therapy wouldn’t have the drawbacks that drugs have. For one thing, this is a more localized treatment, and this kind of therapy would sidestep any drug sensitivity and side-effect issues.

But currently we’re trying to pinpoint those regions in the brain where seizures are occurring with a greater degree of accuracy.

How can you pinpoint or predict seizures?

We record the electrical activity of the brain and then classify the various state transitions between these activities. We then look for differences in pre-seizure states. Sometimes we simply detect the seizures.

What has changed in epilepsy research in the last 20 years?

What’s new about our research, and the best part of the research we’re conducting right now, is that we work as part of a team: neurologists at Toronto Western Hospital, neurosurgeons, pharmacologists, neurophysiologists, physicians, and neural (biomedical) engineers.

What breakthroughs do you think are imminent or potentially imminent?

First, and we’re nearly there: we’re trying to help surgeons cut out the focal region in the brain that needs to be removed to stop seizures. Currently, surgeons just cut as much as they can rather than what needs to be cut, and even that doesn’t guarantee they cut out the right region.

From an ongoing research perspective, we’re trying to understand more about the hyper-excitability that leads to epileptic seizures. This is still an outstanding mystery – and we’re using various models, such as computer models, to answer those questions.

(Read more about epilepsy and research going on at the University of Toronto.)