Canada is facing a tsunami of liver disease and cancer: U of T expert

Published: June 15, 2018

Deaths from liver cancer in Canada have doubled over the past 25 years. And to make matters worse, there’s an epidemic of liver cancer on the horizon if action isn’t taken soon.

While less people are dying from most major cancers – such as breast cancer and lung cancer – liver cancer (hepatocellular carcinoma or HCC) is bucking the trend and heading in the wrong direction.

In 1993, liver cancer rates in Canadian men were five cases per 100,000 population. By 2017 this had risen to 9.9 cases.

For women, rates are much lower, but the trend is the same. In 1993, 1.6 Canadian women per 100,000 were diagnosed with liver cancer; by 2017 this had almost doubled. In hard numbers this means that last year 1,900 men in Canada were diagnosed with liver cancer and 580 women. A total of 950 men died from liver cancer and 270 women.

This is not unique to Canada. A similar pattern is seen in the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia and most other developed countries.

At this week’s Global Hepatitis Summit in Toronto (June 14-17), I will be among a group of liver cancer experts exploring these trends.

The role of hepatitis and obesity

What are the reasons for this increase, and why are they being discussed at the Global Hepatitis Summit? It is because both hepatitis B and hepatitis C are serious liver infections that cause inflammation.

When left untreated, both infections can progress to liver scarring, cirrhosis, liver cancer and, ultimately, an early death.

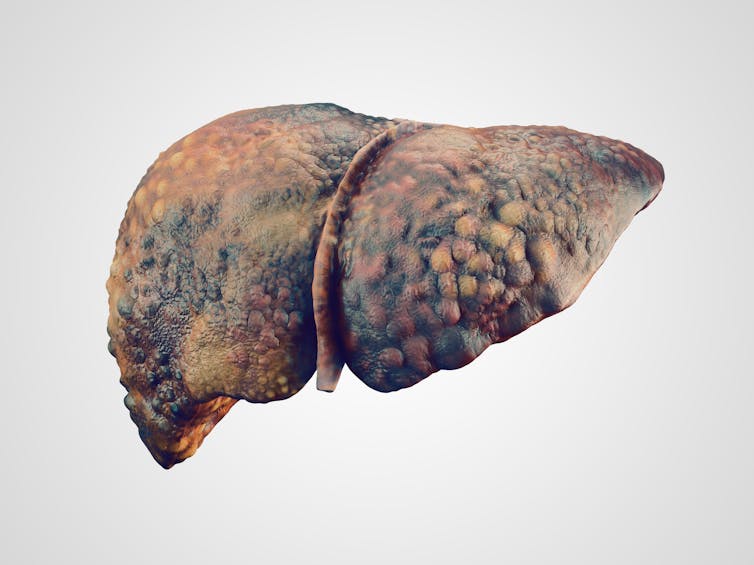

3D image of cirrhosis of the liver (photo by Shutterstock)

Today, there are an estimated 230,000 Canadians with hepatitis B and 250,000 with hepatitis C. Almost half of each group do not know they are infected, which hugely increases their risk of progression to serious liver disease and cancer.

An enormous effort will be needed from provincial and territorial governments – with federal government support – to find, diagnose and treat these missing patients and to link them to care.

Also contributing to Canada’s liver cancer problem is the obesity epidemic: About two thirds of Canadian men and half of women are thought to be overweight or obese.

Some one in five Canadians have some degree of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), which causes inflammation and can progress to cirrhosis and liver cancer.

A lack of liver cancer specialists

Canada’s limited number of liver specialists (less than 100 nationwide) and a few oncologists dealt with around 5,000 cases of liver cancer during 2017.

However, the hepatitis B and C epidemics, combined with Canada’s continuously increasing obesity problem, threaten to drown liver cancer specialists with new cases in the coming decades – with numbers reaching tens of thousands annually over the next 20 years.

We are completely unprepared to deal with such an epidemic of liver cancer. Not only would we be submerged in the sheer number of cases, the financial considerations for provinces and territories and the federal government would be phenomenal.

And many of these liver cancers strike people in their 50s, when they are still of working age. So families are not only in danger of losing a loved one, but possibly the main breadwinner in their family unit.

Not only is Canada’s system of liver specialists being gradually overwhelmed, but there is also a shortage of new liver specialists interested in HCC being trained.

Graduating liver specialists (hepatologists) tend not to specialize in liver cancer. Nor is it a popular speciality in oncology. However, this area is a growing field and there are plenty of opportunities for young physicians to do both practice and research.

Provinces and territories must also take a fresh look at remuneration for liver specialists, who are generally not as well paid as those in other specialities such as gastroenterology.

It may be necessary to develop some special programs to address this issue and boost recruitment in order to deal with the tsunami of liver disease and cancer that Canada is facing.

How to reverse the trend

However, the news is not all bad. Even though Canada’s incidence and mortality rates for liver cancer have doubled over the last 25 years, the actual numbers are much better for Canada than other developed nations. With six new cases per 100,000 population per year, Canada’s liver cancer incidence is lower than Australia (7.4) the U.S. (9.2) and the U.K. (9.6).

A similar pattern is seen with mortality: Canada’s death rate for liver cancer (three per 100,000 population) is less than half that of the U.S. and Australia (both 6.6) and the U.K. (8.7).

Read U of T expert on why all Canadian infants need a hepatitis B vaccination

I believe this is due to our excellent record in finding cases of liver cancer very early, when they can still be successfully operated and treated. The U.S. obviously lacks universal health coverage and the U.K. has a high level of alcoholic liver disease contributing to the epidemic there.

To reverse the increasing trend in liver cancer in Canada and elsewhere, a combination of things will need to occur. First, more patients with hepatitis B and hepatitis C must be diagnosed and treated or cured. Second, new therapies within the next decade should also greatly improve care and prognosis for hepatitis B.

Finally, because obesity in Canada shows no signs of retreating, we will be dependent on new treatments in the pipeline for fatty liver disease. It is unclear at this point how many cases of cirrhosis and liver cancer this will prevent.

Morris Sherman is an affiliate scientist at Toronto General Hospital Research Institute (TGHRI) and Emeritus Professor at the University of Toronto.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

![]()