Canada should remove Mexico from refugee ‘safe’ list, U of T report says

Published: July 15, 2016

A report from the University of Toronto’s international human rights program (IHRP) investigates abuses of human rights faced by people affected by HIV and sexual minorities in Mexico.

Authored by IHRP staff lawyer Kristin Marshall and Maia Rotman, JD candidate at the University of Toronto’s Faculty of Law, the report asks that Mexico be removed from Canada’s refugee ‘safe’ list to protect sexual minorities. Failure to do so could place Canada in violation of its international legal obligation, the report says.

“Canada and the United States are complicit, whether purposefully or not, in the increasing precariousness of LGBTQ lives in Mexico,” says Rotman.

Since 2013 Mexico has been a Designated Country of Origin (DCO), or a “safe” country, for the purpose of refugee-claim determination in Canada, but the report found that the designation poses challenges for people seeking protection in Canada, particularly persecuted members of the LGBTI community and people living with HIV.

“Instead of moving towards the World Health Organization’s 2030 target of eradicating HIV, the disease is increasing among some marginalized populations in Mexico highlighted in our report,” Marshall says.

“Access to healthcare simply is not universal in Mexico – widespread discrimination and barriers exist which can compromise lives.

Canada and the United States can and must do more to insist on and assist with mechanisms that truly respect human rights, real infrastructure that brings those accountable for human rights abuses against LGBTI and other vulnerable populations in Mexico to justice.”

Samer Muscati, director of the IHRP, agrees. “While Mexico has undertaken significant reforms to combat discrimination and human rights violations, people living with HIV, sexual minorities and other vulnerable Mexicans still have little protection when their rights are violated,” he says in a media release.

“Mexico’s failure to investigate and hold perpetrators accountable for violent crimes against marginalized populations is completely at odds with Canada’s designation of the country as ‘safe’.”

Marshall also says that she was both surprised and disturbed by the treatment of migrants in Mexico, and especially those from the LGBTI community in particular.

“This was not exactly part of our research, but did factor in to our consideration of Mexico as a ‘safe’ country nonetheless,” she says.

“Prior to going to Mexico, I had no idea that Mexican law recognizes the fact that migrants suffer harm on Mexican soil, and rather than protecting them from that harm as a signatory to the UN Convention on the Rights of Refugees, or successfully bringing the perpetrators to justice, Mexico acknowledges the injury that migrants experience by providing a “humanitarian visa” – a temporary status to some of the migrants who suffer harm on Mexican soil.”

And many do suffer, she says, but not everyone gets such a visa.

Marshall recalls going to a shelter for migrants while in Mexico. “We went to a shelter that was specifically devoted to migrants who have lost limbs by being pushed off the train as they attempt the dangerous journey across the country and others in need of hospice care to be able to die with dignity. This was beautiful and deeply shocking at the same time,” she says.

Rotman, who will be starting her final year of the JD program in the fall, spoke to Veronica Zaretski about her experiences working alongside Marshall, a career human right lawyer, in Mexico.

What did you learn in the process of putting together the “Unsafe and on the Margins” report?

I was shocked by the discrimination women in Mexico faced in trying to access basic healthcare. It was particularly troubling to hear about the widespread discrimination against transgender women, women living with HIV, sex workers and people who inject drugs.

We spoke with many advocates and activists who reported that women from these groups are facing intersecting oppressions.

In many cases these women are not even able to make it through hospital entrances. Sometimes they would turn away for fear of the police officer stationed at the entrance, or they would be forcibly turned away because they did not have adequate identification - or identification that identified them as their presented gender.

Some who do manage to get through the door are then faced with various injustices and discriminations that impede their access to health.

We heard from a few sources that people living with HIV are required to wait to be the last seen by a doctor and are sometimes asked to bring their own medical instruments in order to not infect anyone else.

One of our most shocking interviews was with a woman who ran a shelter and home for current and retired sex workers in Mexico City. Her stories of discrimination against the young women she cared for were horrific.

She told us of having to resort to badgering and threatening healthcare workers just to get them to give basic lifesaving care to young sex workers, with mixed results. Her experience really brought to light that so many are discarded without any justice because they are made invisible by a system that does not care for them.

On the other side of these horrific stories, though, was also the very inspiring realization that there are so many brilliant and dedicated individuals in Mexico working to make human rights a reality for all. Our research introduced us to many of these individuals, and this report is very much a reflection of their incredible work.

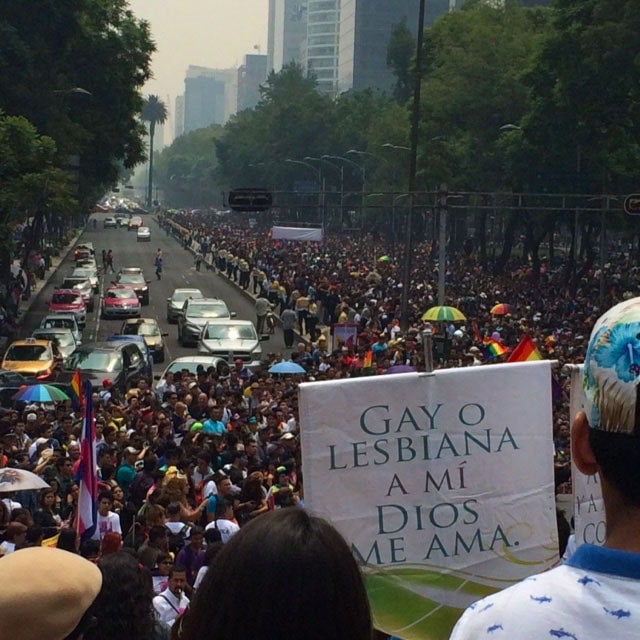

Photo of the Pride Parade in 2016 at Mexico City below by Maia Rotman

Prime Minister Trudeau marched in the Pride Parade, and a few days before that met with President Obama and President Peña Nieto in the Three Amigos summit. He spoke about the leaders’ commitment to protect LGBTQ rights, in the wake of the Orlando shootings. What needs to happen to turn that from talk to action?

The focus on LGBTQ rights at the Three Amigos summit was a huge step forward and is definitely to be applauded. But, it’s not nearly enough. We need to hold our leaders accountable to ensure they are not simply paying lip service to the real struggle for LGBTQ rights.

Canada and the United States are complicit, whether purposefully or not, in the increasing precariousness of LGBTQ lives in Mexico. Border securitization projects, like Programa Frontera Sur, criminalize HIV prevention work.

The failure to provide adequate HIV prevention education is contributing to heightened HIV prevalence rates and vulnerability for sexual minority and marginalized populations in Mexico.

Homophobic and transphobic violence in Mexico is widespread. Because of broad impunity coupled with failures to investigate or even properly label these incidents as ‘hate crimes’, perpetrators are not prosecuted.

LGBTI individuals, especially transgender women, report profound discrimination in the health care system and inability to access consistent and affordable healthcare and HIV treatment.

Our North American leaders need to ensure full, prompt, effective, impartial and diligent investigation of human rights violations perpetrated against LGBTI individuals.

We need our leaders to hold each other to account to abide by international legal obligations. And we need to be sure that any trade agreements signed by the three countries prioritize human rights and do not in any way increase the precariousness of marginalized populations.

The report quotes Justice Boswell as stating that the distinction between DCO and non-DCO claimants is discriminatory and serves to marginalize, prejudice and stereotype DCO claimants like sexual minorities in Mexico. Why do progressive Mexican laws do not translate to actual protection of human rights?

Justice Boswell’s landmark decision found the impact of the DCO label to be discriminatory and our research found the designation itself to be highly problematic.

Canada has identified Mexico to be safe, thereby making it harder for a Mexican claimant to access Canadian protection.

On the face of it, Mexico is seemingly safe. The country has many recently enacted progressive laws and impressive human rights rhetoric. But, there is a problem of implementation. The laws are not translating to actual human rights for the most vulnerable populations. Just about everyone we interviewed in Mexico guffawed when we explained Canada’s DCO system and that Mexico was on the ‘safe’ list.

What are some challenges with Canada’s Designated Country of Origin list? Does the list need to be reworked?

Our research found that despite very progressive human rights legislation on paper, marginalized populations face a reality of discriminatory abuses committed with impunity in Mexico. Likely Mexico is not exceptional in this regard. And, for that reason, the DCO system is inherently flawed and should likely be quashed.

Claimants from DCOs are not entitled to the same procedural rights as claimants from other countries.

Our research reaffirmed our concern that Canada is circumventing its international legal obligations by keeping a “safe” country list.

As a signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention and the 1967 Protocol, Canada is bound by the principle of non-refoulement and has a duty to not discriminate against refugee claimants by reason of their race, religion or country of origin.

If the system remains in effect, however, there are critical adjustments that can be made. An expert human rights panel in charge of designating countries as ‘safe’ could ensure that countries like Mexico do not become DCOs.

The panel would have to evaluate the list on a regular basis to keep up to date with current human rights realities and would have to have mechanisms for taking countries off the list.