Do the Olympics still matter? Yes, says U of T's Bruce Kidd – and here's why

Published: February 6, 2018

With all the ethical and political problems facing the Olympics, do they still matter?

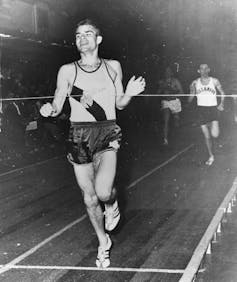

As someone who proudly wears his Olympic heart on his sleeve – I competed in the 1964 Games in Tokyo and have been involved in a variety of roles ever since – I get asked that question all the time, especially when another Games approach. And my answer is still in the affirmative.

While circumstances change, and I’d like to think I make a fresh calculation each time, I still believe the Olympics contribute a net benefit to humanity. I’m excited about the forthcoming Winter Olympic and Winter Paralympic Games in Pyeongchang, South Korea.

For those of us who pursue and watch sports, it’s the only forum where the entire world gets to compete on a multi-sport basis. While it’s the polar countries that excel, the Winter Olympics and Paralympics will attract competitors from an estimated 90 national communities, representing more than two-thirds of the world’s population.

Read this article in Maclean's magazine

In an increasingly privatized sports place, with a hardening monoculture of fewer and fewer sports and competitors, the Olympics provide the greatest range of national and regional accessibility.

Provides support, visibility

For Canadians, it’s the primary place where athletes in the rarely publicized, but culturally important, sports of skiing, skating, luge, skeleton and bobsled have recognized opportunities – and, with few exceptions, the only time Canadian women and para-athletes get any significant support and visibility.

If it wasn’t for the Olympics to stimulate government investment in women’s and para sports and the worldwide coverage to attract advertisers, women and para-athletes would be even more underfunded and invisible in mainstream sports coverage than they are now.

So for those who believe in an equitable, broadly based and accessible sports system, the Olympics provide a very important incentive – and even legitimization.

It’s also fantastic sport, and gives us a chance to see remarkable athletes from all across Canada go up against the best from other countries, and represent Canada to the world. I’ll be glued to my television.

What’s more, the Olympics make a genuine effort to affirm and encourage humanitarian international and intercultural education and exchange – no mean contribution in this increasingly war-torn, nativist and xenophobic world.

Bringing people together

In my long experience, this is real and sets the tone for the millions of sporting exchanges between people of widely different backgrounds that occur around the world throughout the year.

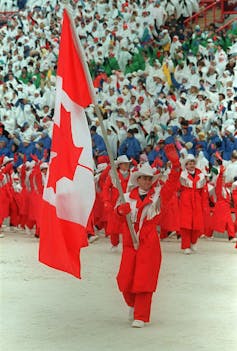

The joint North and South Korean team that will march and compete together in Pyeongchang, and the resumption of communication that it has initiated, is just one example where the Olympics and international sport have brought bitterly divided people into the same room for peaceful exchange.

The Olympics contribute significantly to the development of sports around the world, especially among the poorest countries, distributing a big share of its television revenue – US$509 million from 2017-20.

One priority is sport for refugees. The very first Refugee Olympic Team, made up of athletes from refugee camps in four different countries, competed in Rio in 2016. Many Olympic athletes, such as Canada’s Rosie MacLennan, have been inspired by their experiences to contribute to sport for development across the Global South.

To be sure, the Olympics face a host of daunting challenges, including the ginormous costs of staging Games, corruption in governance, human rights abuses and doping.

The issues are so formidable that fewer and fewer cities are interested in hosting them, and in some liberal-democratic countries, voters have turned back bids. It remains to be seen whether Calgary will actually go ahead with plans to bid for the 2026 Winter Olympics and Paralympics.

Addressing many challenges

But I would also say the Olympic leadership is preoccupied with addressing these challenges. One solution to rising costs is to use existing facilities as much as possible, spread out new facilities, placing them where they are most needed as Toronto did for the 2015 Pan American and Parapan American Games, and reduce seating for spectators, recognizing that most of the world watches on television. The Olympics vigorously tries to prevent and punish doping, as the current spat with Russia readily indicates.

While the Olympics have introduced important reforms in recent years, including transparent financial accounting and an affirmation against discrimination based on an athlete’s sexual orientation, it’s not easy to introduce and implement progressive change in way that keeps the entire world together.

I am enraged by the Russians’ state-directed doping in Sochi and support Canadian Olympic leaders who call for them to be banned from Pyeongchang. Yet I have European friends who fear Russian isolation and applaud IOC president Thomas Bach’s diplomatic gymnastics to balance sanctions and representation.

A big-tent approach requires a low threshold if you want everyone there. If we only competed with countries that shared our values, we would have very few competitors indeed. But it makes the world of Olympic sports very difficult to govern.

I’m quite happy if people continue to be critical of Olympic practices or blind spots – I’m critical of some of them too – but to give up on the project because the international sports world is not perfect would be really short-sighted. It would also deny Canadians an opportunity to participate in, and contribute to, a humanitarian movement that’s still very important.

Bruce Kidd is vice-president of the University of Toronto and principal of U of T Scarborough.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

![]()