English scholar pens sonnets to celebrate 17th-century Dutch art

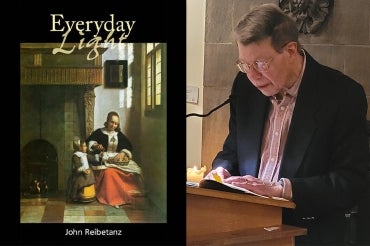

John Reibetanz, a U of T professor emeritus of English, says the sonnet is the perfect tool to capture his thoughts and impressions of Dutch art between 1600 and 1660 (supplied images)

Published: March 21, 2025

As a young boy, John Reibetanz frequently found himself spellbound inside the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.

“I got taken to the Met every two or three weeks, and I was allowed to just find myself in front of painting after painting and wonder, ‘How did these paintings come here?’” he said.

Decades later, the scholar, writer and professor emeritus in the University of Toronto’s department of English in the Faculty of Arts & Science and Victoria College drew on those memorable childhood experiences in his latest collection of poetry: Everyday Light.

The book, celebrated at a recent launch at the Arts & Letters Club of Toronto, is a collection of sonnets – traditionally a 14-line poem that follows one of several specific rhyme schemes – inspired by Dutch paintings from the 17th century by artists such as Rembrandt van Rijn, Frans Hals and Johannes Vermeer.

Reibetanz said he travelled to the Netherlands two years ago and visited more than 20 museums and art galleries to select paintings to include in the collection.

“I looked at so many different paintings, and I chose the ones that had the most relevance to what our culture faces today.”

At the launch, fellow poet and U of T alumnus Jeffery Donaldson noted that a poem is, in many ways, a verbal painting.

“That's part of John's genius – he ‘paints’ in the spirit of the paintings that he is writing about,” said Donaldson, a professor of English and cultural studies at McMaster University. “The poems bring something to them … gives voice to something that is going on, helps them to speak.”

Reibetanz’s poems touch on themes of music, landscapes and ordinary domestic life – all drawn from the paintings he studied.

“It's a period of great efflorescence in art because everybody owned art,” explained Reibetanz. “It's an age of great connection. People are reading each other's poems and looking at each other's paintings and finding inspiration from them.

“There were people who made a very modest living but had 65 to 70 pictures in their house. They were passed from one generation to another. And so, unlike the art of a lot of Europe, which disappeared after the 17th century, Dutch art stayed.”

Allan Briesmaster, a Toronto-based poet and editor of Everyday Light, suggested a “special approach” to enjoying the collection: reading a sonnet, then finding the painting Reibetanz references and then reading the sonnet again.

“The experience is sure to be illuminating,” he said. “It certainly was for me.”

Reibetanz, who has written 18 books of poetry, including Metromorphoses, said in the author’s note of the book that Everyday Light “is an attempt to capture the wildness, the strangeness and utter originality that constitute Dutch art in the triumphant era of 1600 to 1660.”

He said the sonnet was the perfect tool to capture his thoughts and impressions of these great works.

“The sonnet form just opened itself up to me,” said Reibetanz. “A sonnet opens up at the beginning, and then there's complication, complication, complication, and then some kind of resolution.

“That's the way the sonnet worked in the 17th century – it formulated people's thoughts – and still does today.”

While all the paintings referenced in Everyday Light capture Reibetanz, there are a few that have special meaning – so much so that he broke free from the traditional sonnet form, extending his poems with a deliberate break in the stanzas on a separate page.

For example, Vermeer’s Woman Holding a Balance (1662) that features a young pregnant woman holding an empty balance over a table on which stands an open jewelry box, led Reibetanz to write in his poem Grace:

Filled with grace, her cape billows out bell-like,

in a secular annunciation

proclaiming the beginnings of new life,

all human, sprung from human affection.

Rembrandt’s Self-Portrait at the Age of 63 is one of his last self-portraits painted in the months before his death in 1669. About 80 self-portraits survive from his 40-year career. He painted them for different reasons: to practice different expressions, to experiment with lighting effects and to sell to wealthy collectors.

This painting also inspired Reibetanz to extend his sonnet. In his poem A Changed Prospect, he writes:

What do you do when the years have robbed you

of a late love and a beloved son?

You limn the landscape of grief you see in

your mirror: thick paint and dabbed impasto

trace the rutted forehead and weathered nose,

the worn footpaths circling the eyes’ valleys.

The book’s title reflects Reibetanz’s exploration of “what it takes to be responding to the familiar, everyday occurrence of light in their works,” he said.

“So there is a strong sense of everyday light going through the entire volume. It involves getting something, holding on to it, and seeing how the picture corresponds to your sense of life.”