Escape the winter gloom and surround yourself with nature at this new U of T library exhibit

Published: January 29, 2019

Long before Beatlemania, there was beetlemania, the seaweed craze, orchidelerium and fern fever.

Victorians in the mid-1800s were obsessed with the natural world, spawned by an abundance of print material on natural history at price points that could reach almost anyone, from aristocrats to working-class families.

These publications taught people how to grow, preserve and sketch plant specimens they acquired or collected and, in turn, Victorians created their own print material to document the flora and fauna they were observing.

Beginning today, University of Toronto’s Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library will be showcasing its collection of Victorian natural history at Nature on the Page: The Print and Manuscript Culture of Victorian Natural History.

The exhibition is curated by Maria Zytaruk, a U of T alumna and an associate professor of English at the University of Calgary. Her work centres on the history of collecting and the history of museums, particularly with regards to plant specimens and their preservation.

Much like today’s clothing trends, which only become popular when they reach fast-fashion chains, natural history reached widespread popularity when publications were available at a low price, says Zytaruk.

“Victorian natural history didn't proliferate until it could reach down lower into the book market in inexpensively produced handbooks,” she says.

One-shilling guides (pictured above) about everything from ferns to microscopes made nature accessible. They allowed people to bring the wilderness into their homes – even if it was just a modest plant in a soapbox on a windowsill.

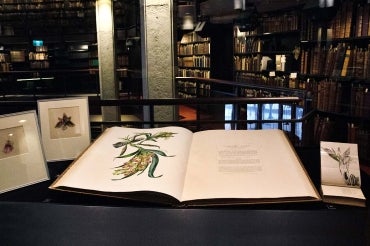

The exhibition includes a number of the mass-produced, one-shilling handbooks, as well as some unique items, including a 38-pound book with life-sized illustrations of orchids.

“It's a beautiful mammoth book. It's like the Audubon of orchids,” says Zytaruk.

Orchidaceae of Mexico and Guatemala by James Bateman would have been sent to a small subscriber base of high-end orchid collectors and people with conservatories, says Zytaruk.

The vast majority of the book was illustrated by women, including Sarah Anne Drake, whose manuscripts are also owned by Fisher library.

“I've really tried to highlight the role of women as illustrators and authors of these books, and as collectors and artists,” says Zytaruk.

Treasures of the Deep by David Landsborough (pictured above, top centre), includes what may appear at first glance to be an illustration of bright pink seaweed. In fact, it fooled Zytaruk when she first saw it.

“As I looked at it more closely I realized it was a specimen of seaweed preserved from the 19th century,” she says.

It got Zytaruk thinking about the number of specimens needed to fill the approximately 100 books that were circulated.

Victorians had preservation in mind when collecting plant and animal specimens, but their obsession had a detrimental effect on the nature they were trying to immortalize, she says.

“They were collecting to preserve, but many species became threatened and some were extinguished entirely – fern species, seaweed species, birds, various plants, native orchids,” says Zytaruk. “There were tensions between preservation and loss.”

Nature on the Page will be on display until April. Free curator-led tours will take place on Feb. 1, 21 and March 14.

(Left) A fern specimen, added to A Systematic Arrangement of British Plants by an enthusiastic reader, and an illustration of an orchid in Orchidaceae of Mexico and Guatemala