Geoffrey Hinton wins Nobel Prize in Physics

(Photo by Johnny Guatto/University of Toronto)

Published: October 8, 2024

Geoffrey Hinton, a University Professor Emeritus of computer science at the University of Toronto, has won the 2024 Nobel Prize in Physics.

Widely regarded as the “godfather of AI,” Hinton shared the prize with John J. Hopfield of Princeton University for foundational discoveries and inventions that enable machine learning with artificial neural networks.

Hinton said he was “flabbergasted” at the honour as messages poured in from around the world.

“I had no expectations of this,” he told U of T News shortly after the win was announced in Stockholm Tuesday morning. “I am extremely surprised and I'm honoured to be included.”

He later told reporters at a press conference he was “in a cheap hotel in California” with no Internet and a poor phone connection when he was notified about his Nobel Prize.

“I was going to get an MRI scan today, but I think I’m going to have to cancel that.”

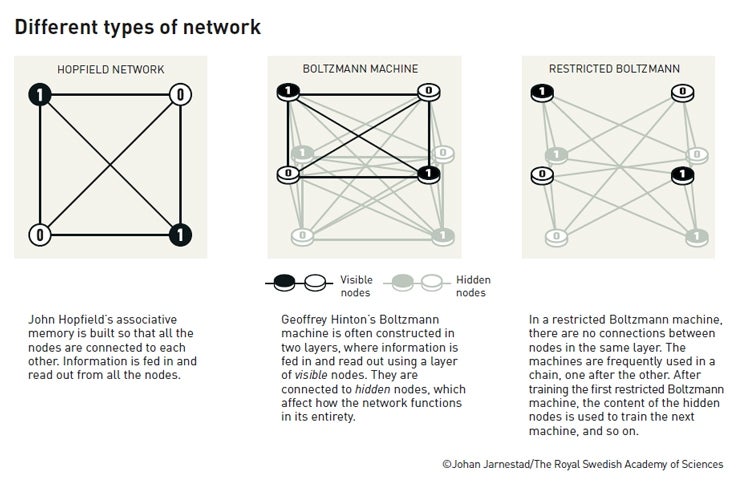

Hinton and Hopfield are credited with wielding tools from physics to advance basic research in the field. Specifically, Hopfield created an associative memory that can store and reconstruct images in data, while Hinton invented a way to find properties in data and perform tasks such as identifying specific elements in pictures.

“On behalf of the University of Toronto, I am absolutely delighted to congratulate University Professor Emeritus Geoffrey Hinton on receiving the 2024 Nobel Prize in Physics,” said U of T President Meric Gertler. “The U of T community is immensely proud of his historic accomplishment.”

Hinton was selected for the high-profile award for his use of the Hopfield network – invented by his co-laureate – as the foundation for a new network called the Boltzmann machine that can learn to recognize elements within a given type of data.

The Boltzmann machine can classify images and generate new examples of the pattern on which it was trained, with Hinton and his graduate students later building on this work to help usher in today’s rapid development of machine learning – a technology that now underpins a host of applications ranging from large language models such as ChatGPT to self-driving cars.

“The laureates’ work has already been of the greatest benefit. In physics we use artificial neural networks in a vast range of areas, such as developing new materials with specific properties,” said Ellen Moons, chair of the Nobel Committee for Physics.

The win by Hinton and Hopfield was covered by media and other organizations around the globe, with The New York Times describing the Nobel committee’s decision as “an acknowledgement of AI’s growing significance in the way people live and work,” and the prestigious journal Nature noting Hinton’s innovations now “form the basis of many state-of-the-art AI tools.”

Hinton joined U of T as a professor of computer science in 1987 after working in various universities in the U.K., where he was born, and in the United States. He went on to be named a University Professor – U of T’s highest academic appointment – in 2006.

Driven by a desire to understand the human brain, Hinton and his graduate students built on his early efforts with an array of developments that paved the way for an explosion in deep learning. One of the first cohort of researchers supported by the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research (CIFAR), Hinton’s work helped catapult Canada to its current status as a global leader in AI development.

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, which awards the Nobel Prize in Physics, noted Hinton persisted with his research even as the scientific community lost interest in artificial neural networks during the 1990s, and ultimately “helped start the new explosion of exciting results” in the 2000s.

Hinton, for his part, said during a U of T press conference Tuesday evening that his achievements wouldn’t have been possible without support for curiosity-based research – something he said Canada was good at.

He added that his shock at winning the Nobel stemmed from the fact that, while his work has drawn on statistical physics, he isn’t a physicist himself – and even “dropped out of physics after my first year in university because I couldn’t do the complicated math.”

He also said that he plans to donate the money associated with the prize to various charities, including one that provides jobs for neurodiverse young adults.

Hinton likened the influence of AI to that of the Industrial Revolution during a virtual press conference with the academy earlier in the day – “But instead of exceeding people in physical strength, it’s going to exceed people in intellectual ability.”

He added that the rise of AI “is going to be wonderful in many respects,” citing health care and workplace productivity as two areas poised to benefit hugely from the technology. “But we also have to worry about a number of possible bad consequences, particularly the threat of these things getting out of control,” Hinton said.

In early 2023, Hinton quit his job at Google and focused on sounding the alarm about the risks of rapid and unfettered AI development. He outlined his reasoning in a 46-minute U of T video last year, urging young researchers to focus their efforts on the emerging field of AI safety – a message he repeated in media interviews following his Nobel win.

He has continued to tackle the issue at lectures and public appearances around the world, including at U of T and at Cambridge University, his alma mater.

“I am thrilled Geoffrey Hinton, an esteemed colleague and dear friend has been awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics,” said Melanie Woodin, dean of U of T’s Faculty of Arts & Science.

“Geoff is an historic visionary whose groundbreaking work in deep learning and neural networks has made U of T and the Toronto region a leading global centre for AI. And it speaks volumes about his integrity that while he helped lay the foundation for the artificial intelligence revolution, he is also one of the leading voices urging that we develop this technology responsibly and ethically.”

Similarly, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau lauded Hinton for his efforts to realize responsible AI development, releasing a statement and writing on X: “Geoffrey, we’re glad to have a mind like yours developing safe and responsible AI for the world.”

Hinton, who is co-founder and chief scientific adviser at the Vector Institute in Toronto, joins an illustrious list of past Nobel Prize in Physics winners that includes Albert Einstein and Marie Curie (who also won a Nobel in chemistry). The prestigious award is the latest in a long list of accolades for Hinton. They include the Association for Computing Machinery’s A.M. Turing Award – widely considered “the Nobel Prize of computing” – in 2019 alongside collaborators Yann LeCun and Yoshua Bengio.

Hinton is the fourth U of T faculty member to win a Nobel Prize over the years.

Sir Frederick Banting and J.J.R Macleod won a Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their work with Charles Best in 1923 to isolate insulin. In 1986, John Polanyi was one of three winners of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the development of the new field of reaction dynamics.

Other members of the U of T community, including several alumni, have received or been associated with the international honour.

Oliver Smithies, a past professor at U of T, was a joint winner of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2007 for discovering the “principles for introducing specific gene modifications in mice by the use of embryonic stem cells.”

Also in 2007, Professor Robert Jefferies shared in the Nobel Peace Prize awarded to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), in which he was a key Canadian representative as an international leader in Arctic science and global change biology.

In 1999, U of T Professor James Orbinski accepted the Nobel Peace Prize on behalf of Doctors Without Borders, which was recognized for its humanitarian work.

Anti-nuclear activist and U of T alumna Setsuko Thurlow accepted the Nobel Peace Prize in Norway in 2017 on behalf the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN).

In 2001, Michael Spence, an alumnus of University of Toronto Schools, was one of three joint winners of the Bank of Sweden Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel for his contributions to analyses of markets with asymmetrical information.

Bertram Brockhouse, who completed two degrees at U of T, was a co-winner of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1994 for the development of neutron scattering techniques for studies of condensed matter.

Arthur Schawlow, an alumnus, was one of three winners of the same prize in 1981 for his contribution to the development of laser spectroscopy.

In 1998, U of T alumnus Walter Kohn was a co-winner of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for development of the density-functional theory.

Former Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson, who received a bachelor’s degree from U of T, won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1957.