Have the Academy Awards had a critical makeover?

Published: March 1, 2018

Over the course of its 90 years, the Academy Awards have been a constant cultural punching bag. Too timid, too mainstream, too predictable, and too white: All of these charges have been levelled at the Oscars, not without justification.

Any awards body that decreed the distinctly mediocre The Greatest Show on Earth as the greatest movie of 1952 in the same year that it denied the sublime Singin’ in the Rain a nomination for the same honour clearly knows how to get things monumentally wrong. And anyone who has traced the long line of Oscar missteps can find many additional opportunities for head scratching.

In the late 1930s, for example, a high point in Hollywood’s production history, the best the Academy could come up with for its Best Picture winners in the years 1936-38 were The Great Ziegfeld, The Life of Emile Zola, and You Can’t Take it With You (the latter at least a Capra film, but second-rate Capra); meanwhile, Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (much better Capra), The Awful Truth, and The Adventures of Robin Hood (not to mention Grand Illusion from France) were never recognized.

Going My Way over Double Indemnity? The Sting trumping Cries and Whispers? Rocky KOing Taxi Driver? Forrest Gump the superior of Pulp Fiction? The choices would be lamentable if they weren’t laughable.

But we continue to care about the Oscars, to invest in their bad decisions and celebrate when the Academy gets it right.

And for those who care about the future of American movies, and how this particular prize, more so than any other, can aid in promoting the profile of quality filmmaking, it matters that the Academy ultimately makes defendable choices.

Assessing this year’s crop of nominees, one can detect certain trends that indicate where the Oscars are heading and why. I offer three, all of them holding out the promise that the Academy is in little danger of making a gaffe on the order of Around the World in 80 Days (1956’s baffling choice for Best Picture) anytime soon.

Trend #1: Auteurs rule

Back in the 1950s, when French critics from Cahiers du Cinéma devised la politique des auteurs, it was considered a revolutionary approach to elevate the film director to the status of the creative wellspring of a film, especially when the film in question came from the factories of Hollywood.

Time has validated the preferences of the Cahiers writers (many of whom would become the driving force behind la Nouvelle Vague, and auteurs in their own right). Now, even casual moviegoers recognize that the name David Fincher or Wes Anderson attached to a new release automatically elevates it to the status of film art. And the Academy has fallen in line with critical orthodoxy.

Rarely does one find that the choices for Best Director are not also the auteurs behind the nominees for Best Picture. If a film is sufficiently accomplished to be a Best Picture contender, it must have been directed by a distinguished filmmaker.

Take this year’s crop of nominees: All five have directed films that are considered leading contenders for Best Picture, and the apparent front-runner, Guillermo del Toro, is the unmistakable visionary responsible for The Shape of Water, the film that received 13 nominations, the most of all the films in contention.

In the bad old days, an undeniable auteur like Orson Welles could see his entire career reduced to a single nomination as Best Director (for Citizen Kane, predictably), and one of Cahiers’ great heroes, and the consummate classical craftsman, Howard Hawks, similarly managed to garner only one nomination from the Academy (and that, inexplicably, for Sergeant York). Charlie Chaplin came away empty-handed, if one doesn’t count the Special Award that he received in 1929 for The Circus. Collectively, Fritz Lang, Sam Peckinpah and Spike Lee have zero nominations. (At least Lee, like Hawks before him, finally received an honorary award as a form of atonement from the Academy.)

But now, the Academy seems prepared to acknowledge the foremost directors of the current generation with nominations in the category, and idiosyncratic talents as diverse as Richard Linklater, David O. Russell, Alexander Payne and Darren Aronofsky won’t suffer the fate of never-nominated Sergio Leone.

Trend #2: Film festivals matter

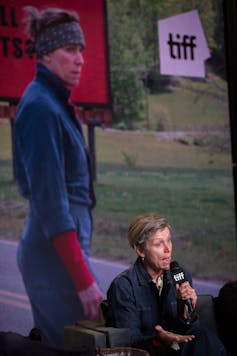

If you ever doubted the predictive power of film festival success, dispel that thought immediately. The Toronto International Film Festival has successfully bestowed its People’s Choice Award winner on five films that eventually also became the Oscar Best Picture of their respective years. It could happen again this year if strong contender (and TIFF victor) Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri pulls ahead of The Shape of Water.

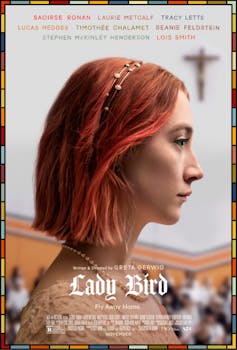

The Shape of Water, for its part, triumphed at Venice, while Sundance, in an impressive showing, featured the premieres of Get Out, The Big Sick, Mudbound and Call Me by Your Name, while Telluride featured Lady Bird and The Darkest Hour. Even Dunkirk managed to squeeze out a film festival appearance via a special IMAX encore at TIFF. Only last-minute entries in the awards race, like Phantom Thread and The Post, bypassed the royal road of pre-release festival premieres, leading to critical hosannas. (And even they got into the act by appearing at the Palm Springs Film Festival after opening commercially, albeit in 2018.)

What this should tell us is that no film that hopes to have a chance of a Best Picture nomination dares skip a berth at a prominent film festival. (Are you listening, Black Panther?) It also signals that the Academy is declaring its allegiance to festival fare, abandoning with ever more steely determination any dalliances with high-budget quality filmmaking.

The Academy is pretty much committed to the festival circuit at this point, and that seems unlikely to change.

Trend #3: Critics’ awards matter even more

As important as film festivals may be to a film’s ultimate Oscar chances, it is the awards from critics’ organizations that tend to determine whether the festival springboard will result in a swan dive or a belly flop. It was not always so.

Beginning in the 1970s, for example, the New York Film Critics Circle began to demonstrate its critical autonomy, often opting for edgier, more auteur-oriented fare, while the Academy stuck to the middlebrow lane.

So, from 1970 to 1979, another high-water mark for American filmmaking, the NYFCC differed from the Academy in their choices seven years in a row, before coming to agreement with Annie Hall. If the taste of the two organizations began to converge with greater regularity in the 1980s, by the mid-1990s they were at variance again.

And even if the winners for Best Picture often diverge about two years out of three on average, the point is that now the Academy’s choice don’t seem any less informed by critical consensus than those of the NYFCC. In other words, if one were to stack up the Academy’s recent choices for Best Picture against those of the NYFCC, one would be hard-pressed to guess which group picked which film.

When the NYFCC went with American Hustle, the Academy opted for 12 Years a Slave, scarcely the more commercial or less critically revered choice. Similarly, last year (to the surprise of many), the Oscar went to Moonlight, with the NYFCC choosing Oscar-bait musical La La Land.

This year, the NYFCC has already cast its lot with Lady Bird, as did the even more choosy National Society of Film Critics. Yet one can scarcely claim the Academy has ignored that critical darling, bestowing five nominations upon Greta Gerwig’s film, all of them in major categories.

The take-away is this: The membership of the Academy is becoming more like that of a critics’ association with every passing year. Looking at this year’s list of nominees, it’s hard to find one glaring misstep.

The inclusion of questionable choices like The Blind Side and Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close (I had to check the internet to verify that one, because even now it seems like an Extremely Obvious Mistake) from several years ago is now a thing of the past, and it will likely stay that way.

Now, some may bemoan the Academy’s shift away from supporting the Marvel universe or the latest Star Wars instalment. (If you fall in that camp, not to worry, there will always be Visual Effects and those two Sound awards that are hard to tell apart.) But ultimately, this is good news for moviegoers.

If people are unlikely to rely on film critics in the digital world order where social media create a din of clashing opinions, then perhaps the viewer looking for guidance can finally trust the Academy Awards. And that means we will never have to worry about a remake of The Greatest Show on Earth making a visit to the Oscars.

Charlie Keil is principal of Innis College, and a professor in the Cinema Studies Institute and department of history at U of T.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.