High levels of 'forever chemicals' found in paper takeout containers: Study

(photo by Jann Huizenga/iStock/Getty Images)

Published: March 28, 2023

From makeup to clothing and furniture, so-called “forever chemicals” are everywhere – including the paper bowls and containers used to package Canadian fast-food meals.

In a recent study published in Environmental Science and Technology Letters, Miriam L. Diamond, a professor in the U of T’s department of Earth sciences and School of the Environment in the Faculty of Arts & Science, and her team examined 42 paper-based wrappers and bowls – often billed as an environmentally friendly alternative to single-use plastics – collected from fast-food restaurants in Toronto.

They were looking for potentially toxic human-made perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), of which there are more than 9,000 in the world.

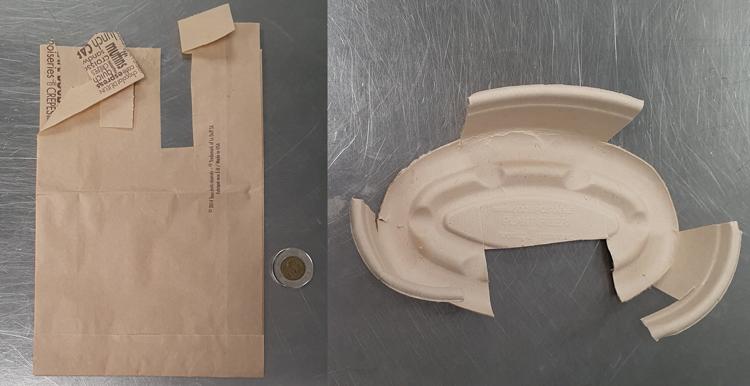

The most abundant compound detected in the samples was 6:2 FTOH, or 6:2 fluorotelomer alcohol – a PFAS that is known to be toxic. Another finding: fibre-based moulded bowls that are marketed as “compostable” had PFAS levels three to 10 times higher than paper doughnut and pastry bags.

Miriam Diamond

“As Canada restricts single-use plastics in food-service ware, our research shows that what we like to think of as the better alternatives are not so safe and green after all,” Diamond says. “In fact, they may harm our health and the environment by providing a direct route to PFAS exposure – first by contaminating the food we eat, and after they’re thrown away, polluting our air and drinking water.

“The use of PFAS in food packaging is a regrettable substitution of trading one harmful option – single-use plastics – for another.”

The research team included Hui Peng, an assistant professor in the department of chemistry, and, from the department of Earth sciences, recent graduates Anna Shalin and Diwen Yang, as well as research associate Heather Schwartz-Narbonne.

Diamond says PFAS eventually end up in our bodies and the environment, where they stay.

“PFAS are complex, persistent and they don’t break down. Whatever molecule is manufactured today will be in the environment 100 years later,” says Diamond, noting these toxic chemicals are found in a host of everyday products and have been linked to adverse health effects, including an increase in cancer risk, thyroid disease, cholesterol levels and decreased immune response and fertility.

“The bottom line is, there’s too much PFAS in the world and not enough restrictions around their use,” she says. “We need to get serious about replacing these substances with safer alternatives if we want to protect our health, and our planet’s health.”

As an environmental chemist and chemical management expert, Diamond is on a scientific mission to determine the most significant sources of PFAS exposure and spur action to limit their prevalence. As she puts it, there would be no “forever” if these chemicals were never used in the first place.

Samples of paper bag and fibre bowl used for takeout food were tested for PFAS (images courtesy of Miriam Diamond)

Diamond saw her research help shape policy last fall when California banned the use of PFAS in fabrics and cosmetics by 2025. This legislation builds on recent studies about PFAS in clothing and makeup that were carried out by Diamond and her colleagues at U of T and institutions around the world.

In a first-of-its-kind paper published in September 2022, the researchers analyzed children’s clothing in Canada and the United States to determine if such apparel is a significant source of PFAS exposure.

They found extremely high levels of these chemicals in school uniforms, mittens and other products marketed as stain resistant. Diamond says because clothing is worn against the skin, there is a higher risk of absorbing and inhaling chemical contaminants – particularly fluorotelomer alcohols, the primary type of PFAS measured in the uniforms.

“We're running an experiment right now on kids’ exposure to PFAS. There's insufficient information on the harm posed by the chemicals that are going into these products,” Diamond says. “I don’t know any parent who values stain repellency over their child’s health.”

Diamond notes that PFAS management is becoming a priority in Canada. In 2021, Environment Canada announced it was gathering evidence to address designating PFAS as a class, rather than as individual compounds as part of the federal government’s chemicals management plan. Such designations are important for enabling efficient regulatory practices. The action includes investing in research such as Diamond’s to collect information about sources of the chemicals and levels in the environment through 2023.

“We know where PFAS is used, but we don’t know what the biggest sources of environmental and human contamination are,” Diamond says.

She adds that exposure science has shown high levels of these chemicals in personal care products. So, Diamond and the team investigated PFAS levels in cosmetics in 2021, testing 231 cosmetic products. They found the highest concentration of PFAS in foundations, mascaras and lip products – particularly those that were labelled “wear-resistant,” “long-lasting” or “waterproof.”

“Focusing our attention on cosmetics as a potentially significant route to PFAS was a no-brainer,” she says. “You’re putting them right on your skin, near your eyes, your tear ducts, on your mouth ... is your beauty worth the risk to your health?”

Next, she is turning her attention to building materials such as outdoor durable paints and sealants for concrete and wood, and textiles used in outdoor settings like patio furniture.

“The problem with PFAS is that it is not labelled as an ingredient, so if you want to limit your use of certain products that contain these chemicals, you usually don’t even know what these are,” says Diamond. “That’s when buzzwords will tip you off – like stain-resistant and waterproof. But this vigilance shouldn’t fall only to the consumer.

“In Canada, we need to strengthen chemicals management to improve the health and safety for ourselves and for the next generations. That means better corporate responsibility and government regulations.”