How one U of T PhD student's dream of exploring space took flight on a balloon

Emaad Paracha, right, snaps a selfie with the SuperBIT team in New Zealand (supplied image)

Published: September 29, 2023

Emaad Paracha's fascination with outer space began at a young age – he even studied Russian in high school as it’s required by NASA to become an astronaut.

And his journey of exploration is only beginning.

Now a PhD student in the Balloon Astrophysics Group at the University of Toronto, Paracha often finds himself liaising directly with the U.S. space agency as he works on some of the field’s biggest challenges.

Working with supervisor Barth Netterfield, a professor in the David A. Dunlap department of astronomy and astrophysics in the Faculty of Arts & Science, Paracha was a key member of the team that launched the Super-pressure Balloon-borne Imaging Telescope, known as SuperBIT, earlier this year.

The telescope’s mission was a success, and the images it collected will help astrophysicists further our understanding of dark matter and the formation of the universe.

“I never really thought once I was graduating that I'd be doing a project like this,” says Paracha, who completed a master’s degree in physics at U of T and a bachelor’s degree in science from U of T Scarborough.

Paracha's responsibilities on the project were varied, from helping build the hardware to writing flight code. Some of his biggest contributions to SuperBIT were working on its autopilot mode, which allowed SuperBIT to take images automatically based on the time and its location, as well as a file program that downloaded images to Earth.

He also helped implement SpaceX's Starlink connectivity for the first time on any balloon mission in the world.

With experience in coding, mathematics, machine learning, artificial intelligence, cloud development and more, Paracha credits his two U of T degrees for giving him the knowledge and skills he needs to perform his work.

“All the tools and resources that U of T and U of T professors have provided, especially the department of physics, have been really helpful,” he says. “It's been great. There’s a reason why I've been here so long.”

Netterfield, his supervisor, says Paracha is a key member of the team.

“Emaad is self-motivated, which means you don’t have to push him and that pushing doesn’t do any good,” he says. “He has lots of cool, interesting ideas and ways of doing things, and generally adds a lot of character to the group.”

In February 2023, Paracha and the SuperBIT team travelled to Wānaka, New Zealand to build, test and launch the telescope. It was the culmination of years of work – with no guarantee the launch would actually take place given strict safety protocols and varying weather conditions.

“I just had in my mind that there was a 70 per cent chance it was going to be scrapped,” Paracha says. “Eventually it came to the point where we were just waiting and waiting and waiting.”

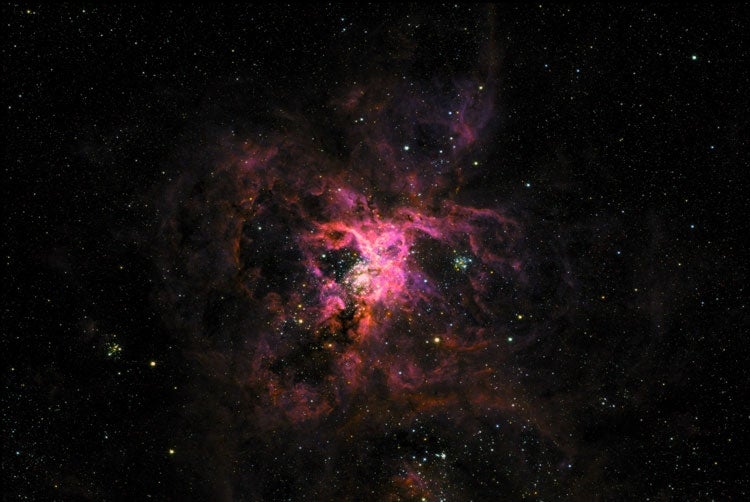

After 13 long hours, SuperBIT was lifted into near space by a NASA Super Pressure balloon that, when fully inflated, is larger than a football stadium. There, it began its mission of photographing distant galaxy clusters.

“It was just a really big relief,” Paracha says. “But also the feeling that the real work begins now.”

Working on balloon-borne telescopes comes with both highs and lows. Forty days into its 100-day journey, SuperBIT was brought down before it could drift over Antarctica. Because of the hilly area and windy conditions on the day of the termination, it was dragged for kilometres along rocky terrain.

Paracha was part of the team that travelled to the Patagonia Desert, on the southern tip of Argentina, a full day’s drive from the nearest city, for the bittersweet job of recovering what remained of SuperBIT.

“The telescope was in shambles,” Paracha says. “But the good thing is we were able to get our data back.”

While SuperBIT will never launch again, the data it collected will help astrophysicists use a process called weak lensing – studying how light bends around distant galactic clusters – to make inferences about dark matter that could improve our cosmological model of the universe.

The more immediate result of SuperBIT’s demise is that it clears the way for Netterfield and Paracha’s next project: GigaBIT. The next generation telescope will improve in many ways on SuperBIT. It aims to rival the resolution of the Hubble Space Telescope with a much wider field of view.

“Emaad is the last man standing. He’s the only one of my students continuing with GigaBIT,” Netterfield says. “If I had to guess, it's because he enjoys the work with an open hand, not a closed fist, whereas my existence is tied up with this thing succeeding.”

The plan is to fly GigaBIT in five years. Paracha will have already completed his doctorate by then – and is keeping his options open when it comes to next steps. He says he sees himself using his SuperBIT and tech industry experience and to move into the field of space technology, where he wants to play a pivotal role in developing tools that push the boundaries of human exploration and scientific understanding.

“There are so many different problems I want to solve in space tech, like communications, better edge computing and computer architecture design, and both software and hardware design,” Paracha says. “So that's the path I want to take.”

Above all else, Paracha hasn’t lost sight of the goal he’s had since he was a teenager: becoming an astronaut. In his downtime, Paracha loves to travel and photograph iconic landmarks featured on currency of different countries. So far, he's visited 10 countries and taken more than 60 pictures, showcasing them on his website. He already has in mind the finale for the project.

“If you look on the back of a Canadian five-dollar bill, it's the Canadarm in space and an astronaut,” Paracha says. “So maybe I'll go there and take a picture with that.”