Mapping the city: how green space could make for happy kids

Published: August 5, 2016

Mapping the City is an ongoing series on the stories we can tell about people and places in Toronto through maps created by University of Toronto students and faculty.

Read part one: how transit can fix access to jobs

Read part two: what Toronto's waterways can tell us

Read part three: smart transport data pave the way for a driverless future

Read part four: busting conventional wisdom on food deserts

In this fifth instalment, U of T News writer Romi Levine profiles the work of Cosmin Marmureanu and Professor Scott Davies.

Living in a concrete jungle like Toronto can be suffocating sometimes – the noise, traffic and pollution can seem inescapable. The city’s parks – big and small – serve as an oasis from the chaos.

Anyone who’s taken a quick stroll through a leafy park on their lunch break can attest to that.

It should come as no surprise then, that the correlation between health and proximity to nature has been studied numerous times. Not only can this closeness to green space make you feel healthier, one study even says you’ll feel richer with a few extra trees in your neighbourhood.

But can access to trees and parks make you a better student?

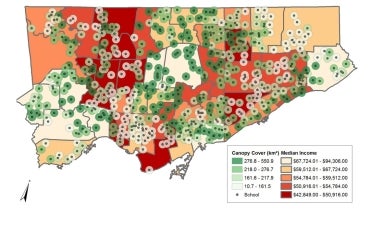

That’s what Cosmin Marmureanu, a PhD student at OISE, is trying to figure out. He’s working alongside Professor Scott Davies to map out the relationship between a school’s physical surroundings and student achievement.

Though it’s still early in the research process, Marmureanu says he has “found medium strength correlations between suspensions and expulsions and the amount of vegetation around the schools.”

As a summer student and research assistant for the Toronto District School Board (TDSB), Marmureanu has access to plenty of data on the location of trees and parkland and its proximity to schools. The school board has shown interest in his research and has published papers of their own on the benefits of bringing vegetation closer to schools and teaching kids about the environment.

“Greening is now a priority for them and the Ontario government in general,” says Marmureanu.

The challenge of putting this plan into practise is convincing school administration of why it’s important, he says.

“A lot of the time the grounds aren’t the first thing the principal is worried about – they’re worried about student achievement and school safety,” Marmureanu says. “It’s not something they necessarily think about – to get them to realize ‘hey, if you had a green space for students to each their lunch, [students] may be more relaxed and less aggressive as a result.’”

Davies says there are, of course, other factors at play – such as the quality of upkeep in the school, the reputation of the school and the neighbourhood it’s located in and whether or not students actually have access to the green space.

Marmureanu says he’s also look at how the ways students get to school affects their performance.

“If they’re spending 40 minutes in a subway tunnel – are these kids different from the kid that walks 15 minutes outside in fresh air in a densely vegetated neighbourhood?” he asks.

For Marmureanu, his interest in the topic is also personal. He grew up downtown – close to Spadina and Bloor, but moved further north to leafier Bathurst and Eglinton. The change “does make an impact,” he says.

Davies says the use of maps for education research is a relatively new idea, but a useful one.

“Mapping has the potential to tell a lot more stories,” he says.

And Marmureanu adds: “It sends a much stronger message than a pie chart or a graph.”

This cross-discipline pursuit is something Davies wants to continue fostering.

“I want to form a partnership with people across U of T who also have an interest in how geography and education overlap. For example, there are guys in engineering who are interested in air quality and how air quality in the city varies substantially – and we want to map that onto schools,” he says.