Murder they wrote: U of T professor on what killers reveal through their writing

Published: June 16, 2017

It started with a letter left by a serial killer.

University of Toronto Professor Marcel Danesi was given the letter by a former student who was studying it as part of a cold case research initiative at Western University.

Danesi knew nothing about the case, but through reading the letter, he was able to uncover details about the killer.

“Look at this sentence here – it's connected to this one and underneath it is a rhetorical structure,” says Danesi, who is a professor of semiotics and anthropology at U of T's Faculty of Arts & Science. “That's how we reveal ourselves when we speak – not on the surface but below it. We project ourselves onto our writing.”

While Danesi had a casual interest in the writings of famous murderers like Jack the Ripper, it was this letter that encouraged him to dig deeper.

He teamed up with the instructor of the Western University cold case initiative, Michael Arntfield, who is a criminologist and former cop, eventually turning their fascination with the mind of murderers into a book – Murder in Plain English: from manifestos to memes – looking at murder through the words of killers.

Combining semiotics with criminology, Danesi and Arntfield brought complementary perspectives to the book. Arntfield dived into the facts, and Danesi made connections with fiction.

“I look at it as a performance, an act… the line between art and crime seems to be a very thin one, indeed,” says Danesi.

Marcel Danesi also teaches a course on forensic semiotics at U of T, linking crime with history and culture (photo by Romi Levine)

People’s fascination with stories about murder dates back to the ancient Greek tragedies and biblical stories. That’s thousands of years' worth of writing that give context to today’s real-life crimes.

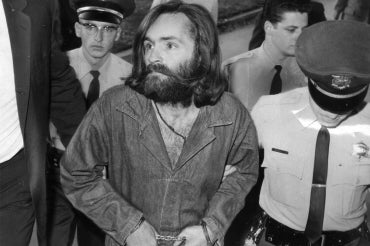

“We started with Cain and Abel. If you work through Shakespeare, you work through Machiavelli, and you come up to today [to killers like] Charles Manson, you've got a portrait of the dark side of humanity,” says Danesi.

Patterns emerge when one looks at the writings of murderers in this way, says Danesi.

“Murder is a puzzle – a mystery. The process of thinking is the same. Who did it? How do I get a solution, and if you don't get one, we're left in a state of angst and discomfort,” he says.

For example, killers have different narrative styles depending on their motive.

A murderer who considers his or her crime as a heroic, self-righteous act – like the Zodiac Killer – will depict the crimes in writing or sketches with graphic detail, Danesi and Arntfield write. In contrast, a person who considers the deadly action as an act of revenge will provide “little or no detail.”

Exploring the prose of killers has taken a shocking turn in the age of social media, says Danesi.

Researching the book involved exploring the dark corners of the Internet: “The scariest thing I have ever seen in my life,” he says. “The Internet today is where we represent crime, where we live, relive, enact it, enjoy it.”

There have been many cases where acts of murder are bragged about online.

“Sometimes we use social media – especially Facebook – as a diary, as a confessional, a way of exculpating oneself,” says Danesi.

Beyond confession, Danesi and Arntfield write, the Internet becomes a “channel for self-expression,” an opportunity for people – including murderers – to leave their mark in cyberspace.

While the serial killer case that originally sparked Danesi's interest remains unsolved, he hopes this exploration of the relationship between crime, history, literature and culture – what he calls forensic semiotics – can play a more important role in criminal investigations.

“Right moves around and so does wrong – those blurry lines is where, I think, a knowledge of the history of the crime, crime writing and meanings of crimes throughout the ages can inform or shed light on the horrific behaviours we see today,” he says.