A ray of hope on World AIDS Day for Canadian immigrants

Published: December 1, 2017

It’s World AIDS Day and this year, I am moving beyond remembering loved ones. I am shifting to a forward position and a distinct political hopefulness.

My wish on this World AIDS Day is for Canada to change how HIV is dealt with in its immigration system. Specifically, I would like to see the nation change how it makes inadmissibility decisions about people with HIV who apply to live in Canada.

This would be done through the Department of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship. It would involve changing specific institutional practices, including the collection and circulation of HIV-related data from prospective immigrants.

The imperative for my research is to demystify social institutions like immigration so that we can explore and understand how things happen. As an interdisciplinary professor in health and social justice, and as a former social worker in a woman’s sexual health communitiy, I work to detect institutionally arising inequities.

For the past 15 years, I have been involved in AIDS work. I have worked in the Horn of Africa and parts of Canada in direct support. My life and lives of people I care about, some of whom cannot immigrate to Canada because of their HIV status, are deeply affected by this infection and its unfortunate pernicious social standing. I work with teams to use creativity and critique in equal measure to produce do-able ideas for remedying some of these inequities.

Using creativity and critique

This is precisely what I have done for Canada’s mandatory immigration HIV testing policy. The policy was enacted in 2002, but not ever reviewed until my work.

The policy acts as a filter. It screens for HIV and sorts people with HIV out (with some exceptions). HIV is discovered in the medical examination that all applicants for permanent residency must undergo at regular intervals. Most of these exams happen outside of Canada in contexts that Canada cannot monitor.

My motivation for assessing how this policy functions in everyday lives was because of the disconnect between immigrant people’s everyday social experiences through Canada’s imposed HIV testing, and the official representations of these experiences.

I formed alliances with racialized women with HIV from the Global South coming through the Canadian refugee ajudication system. Through them, I learned of the contrast between what actually happened in their lives with immigration medical processes and what is officially understood to have happened as documented in national government reports.

I set out to understand how this dissonance was happening. All persons aged 15 years and older who request Canadian permanent residence, such as refugees and immigrants, are required to undergo HIV testing. Tuberculosis and syphilis are the two other conditions for which people receive mandatory screening.

I produced the first social science exploration and critique of the medical, legal and administrative context governing the immigration to Canada for people with HIV. I identified both inequities and levers for change by using a feminist ethnographic policy analysis.

An immigration HIV test catalyzes the state’s collection of medical data about an applicant. These are entered into state decision-making about the person’s inadmissibility to Canada.

The good news on HIV policy

As it turns out, the HIV policy and mandatory screening ushers in a set of institutional practices that are highly problematic for prospective immigrants with HIV infection, the Canadian state and what is means to be Canadian more broadly. Avoidable inequities have been happening for 16 years, and they are ongoing.

The good news is that policies can be adjusted.

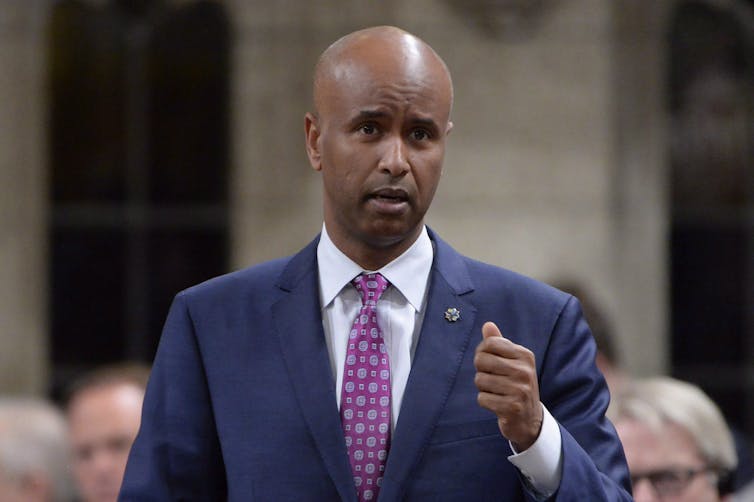

People with disease and disability, and their advocates, recently met with Immigration Minister Ahmed Hussen to discuss and plan a future course of action.

And we have recently learned that Hussen has said “current medical inadmissibility rules for newcomers are out of touch with Canadian values and need to be reformed.”

Canada’s Immigration Minister Ahmed Hussen says current medical inadmissibility rules for newcomers are out of touch with Canadian values and need to be reformed (photo by Adrian Wyld/The Canadian Press)

It was acknowledged that the ways in which medical inadmissibility decision-making is informed and practised are outdated. This certainly applies to HIV/AIDS, a chronic and manageable disease and an episodic disability, in the Canadian context.

We see that HIV infection is scrutinized more and differently than any other health condition through the immigration process, where we see layers of institutional directives, guidelines and practices in place governing HIV/AIDS. A core problem with the HIV testing policy is that it’s not informed by or reliant upon the most up-to-date scientific knowledge..

Democracy depends on how we talk to each other. Research on the social determinants of health shows us that we all live better lives in egalitarian societies. Part of how to achieve such societies is how we talk and listen to each other.

What sort of public spaces can we create to hear and be heard on matters related to the Canadian immigration system and medical inadmissibility decision-making? Opportunities are preciously few.

A roundtable on immigration and disease is needed

I propose a roundtable on immigration, disease and disability in which I bring to the table the most up-to-date scientific knowledge about immigration and HIV. We could invite Harvard’s Professor Michael Sandel to join, because he also asks critically important questions about immigration (and sparks debate to collectively contemplate answers), as well as my colleagues at the Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network. When can we meet to discuss immigration and HIV?

The World AIDS Day flag flies on Parliament Hill in Ottawa last Dec. 1 (photo by Justin Tang/The Canadian Press)

Together in class, students and I have used the research record to examine the human rights implications of mandatory immigration HIV testing in Canada. We have done the same regarding the ethical and material consequences of medical doctors being asked to work in ethical problematic ways within Canada’s immigration system.

Just as other immigrants to Canada do, those with HIV will contribute to our society in myriad ways. Having interacted with thousands upon thousands of people with HIV over time and across space and place, they are among the most resilient and hard-working people I have met, which I attribute to the experience of personal suffering and knowledge of the larger social and political history of HIV/AIDS, not to mention their place within it.

This is precisely the sort of immigrant that Canada wants and indeed welcomes.

I am committed to a process in which we can talk with and listen to each other on matters of immigration and disease as they relate to HIV/AIDS. The moment is upon us to work with the most up-to-date scientific evidence to produce a medical inadmissibility decision-making system unfettered by inducing harm.

Laura Bisaillon is an assistant professor in the health studies program of the department of anthropology at the University of Toronto Scarborough.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.