Sign language needs policy protection in Ghana: U of T expert

Published: January 22, 2019

In 1957, when Ghana gained independence from British colonial rule, African-American educator Andrew Foster established the first school for the Deaf in Ghana.

In so doing, Foster consolidated and echoed Kwame’s Nkrumah’s independence day declaration of freedom for Ghanaians. While Nkrumah championed African independence movements across the continent, Foster, a graduate of Gallaudet University in Washington, is the man who modelled equal education opportunities in Ghana.

Today, Ghana has about 16 schools for the Deaf. However, equal educational opportunities elude Deaf people in Ghana and students encounter many challenges. Chief among them is the fact that Ghana has no formalized sign language policy and therefore doesn’t systematically or adequately fund sign language services in schools for Deaf people.

Ghana urgently needs an official Ghanaian Sign Language (GSL) policy. Such a move has the potential to humanize Deaf education and alleviate the linguistic discrimination that Deaf students face. Furthermore, the work of GSL educators with Deaf students would finally find the support it needs and deserves.

Multiple sign languages in Ghana

People who take hearing for granted may not have considered the fact that sign languages are languages and require safeguards – just like spoken languages, for the sake of people and communities who rely on them.

As a doctoral researcher of language policy, I study how Ghana implements educational language policy for speakers of minority languages.

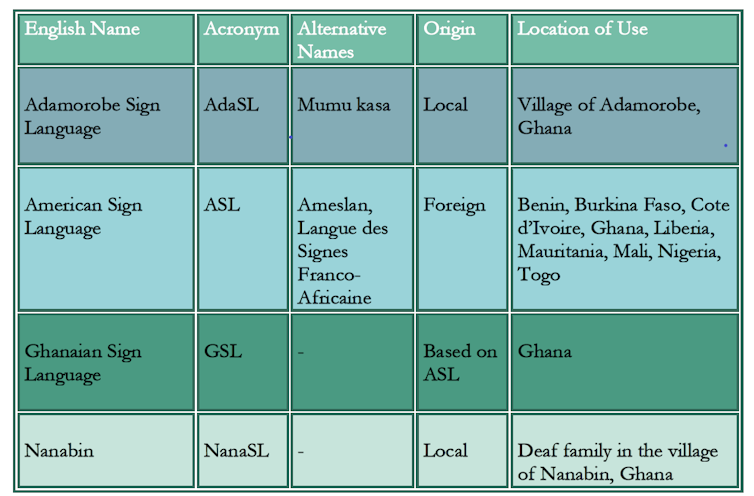

In my research with sign language professionals, I have discovered that just as a multitude of spoken languages exist in Ghana (81 in total), the Ghanaian Deaf community is also linguistically diverse.

Sign language researcher Victoria Nyst has identified four sign languages in Ghana. Ghanaian Sign Language (GSL) is widely used in schools and is a spin-off from American Sign Language (ASL). But GSL incorporates some locally constructed signs.

GSL is estimated to be used by the majority of Deaf people in Ghana. But statistics about the Deaf in Ghana are not well documented.

The Ghana National Association for the Deaf (GNAD) says approximately 0.4 per cent out of Ghana’s population of almost 29 million is Deaf, or 110,625 people; by contrast, the Ghana Statistical Service, reports 211,712 as Deaf.

Research shows that sign language is often viewed as an aberration in Ghana. The Deaf are often derogatorily referred to as mumu, meaning dumb.

In this way, a mainstream Ghanaian way of seeing equates deafness and sign languages to a defective way of being and speaking.

No official sign language policy

In Ghana, the Persons with Disability Act, 2006 (Act 715) enshrines the rights and treatment of Persons with Disability (PWDs).

Yet when compared with regional and global disability legislations, Act 715 is seriously deficient for many reasons – among them, the fact that this act provides no policy pertaining to GSL.

Researchers have called for the Ghanaian government to strengthen local policy for PWDs and to fully conform to provisions outlined in the United Nations’ Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD).

Ghana ratified this convention in 2012, but the country has yet to follow UNCRPD measures and protections to support sign language learning and promote the linguistic rights and identity of deaf communities.

Schooling challenges

Due to inadequate interpretation and translation services in Ghanaian schools for the Deaf, Deaf students gradually forfeit schooling.

Schools serving Deaf students in Ghana have developed in a provisional and stop-gap fashion. Schools offer varied levels of academic instruction and vocational skills training, but Deaf students receive the same instruction and national level assessments as their hearing counterparts and it’s up to the teachers to make it work.

Thus educators in schools for students who are Deaf work in a context common for many minority languages – as language policy researcher Terrence Wiley names it, a “null policy” context, with language needs met with a significant absence of policy. Educators develop de facto policies and strategies to address gaps and promote their students’ academic, social and emotional welfare to lessen marginalization the students experience.

Using GSL to resist ‘disciplinary power’

Educators and the Ghana National Association of the Deaf (GNAD) are challenging stereotypes and empowering Deaf students to participate in policy surrounding their welfare.

For example, GNAD created a drama using GSL before the 2016 Ghanaian elections to promote awareness of civic rights. In the drama, Deaf people both taught the public about signing as a valid mode of communication and about how to vote.

The creation of GSL dictionaries for use offline and online is another instance of unofficial language policy and planning.

The recent introduction of sign language into a mainstream school curriculum is an unprecedented attempt by sign language educators to break communication barriers between Deaf and hearing people in Ghana.

But the fact that instruction in Ghana’s specialized schools for the Deaf is still based on curriculum for hearing schools illustrates that Ghana’s language policy is still being used as what language policy researcher James Tollefson calls “a form of disciplinary power.”

This is to say the institutional neglect of a language policy supporting the needs of Deaf people continues to serve as a means of differentiating the Deaf from the hearing.

Much more can and must be done to recognize GSL. The Ghanaian government must implement accessibility standards to counter the alienation Deaf students face.![]()

Mama Adobea Nii Owoo is a PhD student at the University of Toronto's Ontario Institute for Studies in Education.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.