Stephen Bannon's world: U of T expert on dangerous minds in dangerous times

Published: July 26, 2018

Stephen Bannon, the rabble-rousing populist and alt-right enabler shockingly brought to the White House by Donald Trump, said the following to a gathering of the Front National in March: “Every day, we get stronger and they get weaker.…History is on our side.”

Is it true?

Bannon has not been in the White House for almost a year, yet Trump seems to be far more of a Bannonite today than he was when Bannon had an office in the West Wing, and seems to get more Bannonite with each passing day. Bannon himself recently visited Europe, where he’s planning a European right-wing “super-group.”

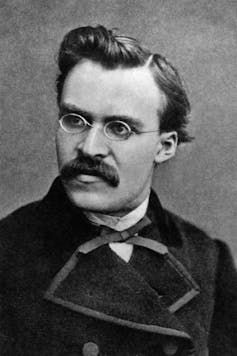

As the far right returns to the scene, so do worries about the possible ideological relevance of vehemently anti-liberal and anti-egalitarian thinkers like Friedrich Nietzsche and Martin Heidegger – whose influences live on.

In the contemporary academic world, it has been widely assumed that Nietzsche and Heidegger are intellectual resources for the cultural and philosophical left, but in a context where the right and far right are newly resurgent, this assumption requires further scrutiny.

Dangerous philosophers

As I suggest in my new book, Dangerous Minds, intellectuals need to be far more alert than they have been in the past to potential far-right appropriations of these powerful but dangerous philosophers.

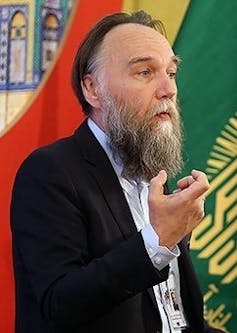

Consider as well two writers of the radical right who have been warmly embraced by the contemporary alt-right: Julius Evola and Aleksandr Dugin. Evola, the Italian baron and monocled proponent of über-fascism, the inspirer of black terrorism in Italy and an explicit disciple of Nietzsche, articulated a vision of caste-based Nietzschean neo-aristocracy.

Charles Clover, in an illuminating recent book, writes that Evola “believed that war was a form of therapy, leading mankind into a higher form of spiritual existence.”

‘Man should be overcome’

Recently, it’s come to light that Heidegger was very much attuned to Evola as a fellow critic of modernity. The modern-day Dugin – himself a disciple of Evola – presents himself as a Russian Heidegger and is published by two white-nationalist presses (Arktos and Richard Spencer’s Radix).

In April 2014, Dugin was asked on Russian TV: “Is there a philosophical quote that is especially dear to you?” Dugin responded: “Yes: Man is something that should be overcome.”

Dugin didn’t specify the source of this quote, but anyone with any acquaintance with the philosophical novel Thus Spoke Zarathustra knows that it’s Nietzsche.

In the same interview, Dugin stated: “The essence of the human being is to be a soldier.” There are texts in which Dugin presents himself as a prophet of a “new aeon” that “will be cruel and paradoxical,” involving slavery, “the renewal of archaic sacredness,” and “a cosmic rampage of the Superhuman.”

He celebrates “hierarchical, vertical, ‘heroic,’ and ‘Spartan’ values.”

Such views capture quite well why the thinkers expressing these views are committed, in a faithfully Nietzschean spirit, to the root-and-branch rejection of the horizon of life embodied in liberal, bourgeois, egalitarian societies.

Liberalism is ‘dehumanizing’

Since the Enlightenment, there has been a line of important thinkers for whom life in liberal modernity is felt to be profoundly dehumanizing. Thinkers in this category include, but are not limited to, Nietzsche, Heidegger, Joseph de Maistre and Carl Schmitt.

For such thinkers, liberal modernity is so degrading that the French Revolution and its egalitarianism, traceable ultimately back to the Protestant Reformation, should be undone if possible. For all of them, hierarchy and elitism are more morally compelling than equality and individual liberty; democracy is seen as diminishing our humanity rather than elevating it.

We are unlikely to understand why fascism is still kicking around in the 21st century unless we are able to grasp why certain intellectuals of the early 20th century gravitated towards fascism – namely, on account of a grim preoccupation with the perceived soullessness of modernity, and a resolve to embrace any politics, however extreme, that seemed to them to promise “spiritual renewal,” to quote Heidegger.

For these thinkers and their contemporary adherents, liberalism, egalitarianism, and democracy are a recipe for absolute mediocrity and spiritual emptiness, and hence for a profound contraction of the human spirit.

Liberal democracies on the defensive

For the political-philosophical tradition within which Nietzsche and Heidegger stand, the French Revolution brought about a world in which authority resides with the herd, not with the shepherd, with the mass (the “they”), not with the elite, and as a consequence, ultimately the whole experience of life spirals down into unbearable shallowness and meaninglessness.

Ferdinand Mount, in a recent New York Review of Books essay on Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, correctly writes that Nietzsche revered Goethe because “only Goethe had treated the French Revolution and the doctrine of equality with the disgust they deserved.”

Of course, Richard Spencer famously said that he was “red-pilled” by Nietzsche – the alt-right lingo meaning that Nietzsche opened his eyes to the truth of fascism.

All of this might have seemed irrelevant during the past 70 years, from about 1945 to 2015, when fascism was utterly discredited.

It doesn’t seem irrelevant today.

On the contrary, liberal democracy seems to be increasingly on the defensive. Today we have Trumpism and Bannonism in the U.S.; Putinism in Russia; Orbánism in Hungary; Erdoğanism in Turkey; Xiism in China; Modiism in India; Duterteism in the Philippines.

Admittedly, none of these leaders are as bad as Hitler or Mussolini or Stalin. But at the same time, none of them are guardians of liberal democracy.

Roger Cohen recently published a New York Times op-ed on the rise of quasi-authoritarianism in Hungary and Poland in which he quotes a former Polish foreign minister’s expression of disdain toward “those who believe history is headed inevitably toward ‘a new mixture of cultures and races, a world made up of cyclists and vegetarians, who only use renewable energy.’”

Politics can generate havoc

The project of populist nationalists in Poland and Hungary is to defend what they take to be European Christian civilization from such pathetic wimps. This, one should not fail to recognize, is a 21st-century version of Nietzsche’s story of the last men who care only about material betterment and lack for any higher aspirations, shuffling through life without anything genuinely meaningful to live for.

Politics always has the potential to generate havoc or worse. The stakes are perhaps particularly high in a political world as unsettled as ours: where technological change is so head-spinningly rapid; where the boundaries between different societies and cultures are being renegotiated on such an epic scale; where the internet lets loose political passions so little inhibited by norms of civility; and where the most powerful man on the planet is someone as volatile as Donald Trump.

Bannon sought to encapsulate the new zeitgeist with a memorable line: “We are witnessing the birth of a new political order.”

We have to take with deadly seriousness the possibility that this is actually the case, and equip ourselves intellectually for a fully robust defense of liberal democracy.

Ronald Beiner is a professor of political science at the University of Toronto and a fellow of the Royal Society of Canada.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

![]()