Twins in space: U of T expert on how space travel affects gene expression

Published: January 10, 2019

Researchers have had a rare opportunity to see how conditions on the International Space Station translate to changes in gene expression by comparing identical twin astronauts. One of the twins spent close to a year in space, while the other remained on Earth.

The environment of the space station induced changes in gene expression through a process called epigenetics.

NASA scientists already know that astronauts will be affected differently by the physical stresses they experience. Studies of astronauts’ genetic backgrounds might explain why some are more susceptible to health problems when they come back to Earth. These findings could translate to personalized preventive measures for the vulnerable astronauts.

Surprisingly, it seems that these discoveries could also lead to therapy development for common syndromes affecting us on Earth.

NASA has been studying the consequences of space travel on the human body since the dawn of the space age. At a news conference held approximately a week after arriving at the International Space Station (ISS), Canadian astronaut David Saint-Jacques said he felt a “little congested” and “had a big red puffy face … like the feeling you get hanging from the monkey bars.” The basis for this uncomfortable feeling relates to fluid redistribution from the lower to the upper body.

Health after long space missions

The health effects that result from long missions in space are not well understood. Overall, astronauts remain in excellent mental and physical health relative to the general population, even after their return from long-term missions. And yet, the health consequences of such missions have been recognized, including cardiovascular deconditioning and vision problems, the causes for which are being investigated.

NASA scientists are exploring how gene expression – the way DNA is converted to tissues – changes in response to the environment inside the ISS. The field of epigenetics describes mechanisms through which environmental factors, like microgravity, relatively high carbon dioxide levels and possible surges in radiation alter the way DNA is read.

Researchers also want to know how each astronaut’s unique DNA will determine their response to the space station environment. Right now, of the 37 studies under way in the space station, three focus specifically on genetic research.

Two of a kind

Preliminary results of the exceptional study of identical twin astronauts support the idea that space travel can affect gene expression in different organs. From 2015 to 2016, astronaut Scott Kelly was aboard the ISS for a consecutive 340 days. His twin brother Mark stayed on Earth. Scott’s basic genetic code was not altered, but the environment of the space station affected the way in which this code was converted into tissue.

According to one of the lead scientists in the twin study, Christopher Mason, these changes occurred in important biological pathways relevant to bone formation and the immune system. The gene expression changes were categorized with respect to possible risk, “as low, medium or high.”

Low-risk changes to gene expression (approximately 93 per cent of all the changes) reset to normal when Scott returned to Earth. Possible medium- to high-risk changes didn’t reverse after six months and “are changes that we’ll want to keep an eye on,” according to Mason. For example, there are expression changes that lead to the immune system being on “high alert,” says Mason.

Although the study of identical twins provides the best evaluation of space effects on gene expression, there are not too many twin astronauts around.

Validation of the findings in the Kelly twins will, by necessity, involve studies in other astronauts. Right now, these validation studies are happening on the International Space Station as liquid biopsies (cell-free DNA and RNA samples from blood) are collected for analysis. But the experiments on the twins really provided a “springboard for all of these subsequent studies,” says Mason.

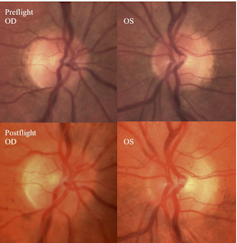

Vision changes after missions

Previous studies of eye health in a group of astronauts suggest that not all astronauts will respond the same way to life on the space station. Astronaut ophthalmic syndrome is a condition that affects some astronauts. These ocular changes are classified by NASA “as a significant risk for human space travellers,” and include changes to the lens and shape of the eye.

In some cases, astronauts with excellent vision before space flight “come back needing to wear glasses,” says Scott Smith, the lead nutritional biochemist at NASA.

“We saw chemical differences in blood samples (from astronauts) before flight, so we started to look at genetics.”

Seventy-two astronauts provided blood samples for this study. On analysis, the research findings suggest that each astronaut’s genetic background plays a role in determining their eyes’ vulnerability, or epigenetic response, to detrimental triggers in the space station.

Space eyes and Earth wombs

This research means that certain astronauts could be warned of their personal risk of developing vision problems during long space missions. Better yet, personalized preventive measures or personalized medicine could be discovered and implemented for those with the greatest risk of disease.

“Virtually all the work that NASA does has implications for the general population,” says Smith.

Ophthalmic Syndrome in astronauts is related to another, much more common health problem here on Earth. It turns out that the same genetic variants and changes in serum factors that are associated with ocular problems in astronauts are also connected to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), a form of infertility in women.

PCOS affects up to 10 per cent of women. A genetic component for this syndrome was previously suspected.

Genetic and epigenetic studies in astronauts promise to provide astronauts with personalized medical interventions while in space. And they could also provide those of us on Earth with potential therapies.![]()

Christine Bear is a professor in the University of Toronto's Faculty of Medicine.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.