U of T expert on how drug ads leave Canadians in the dark about safety risks

Published: September 5, 2018

When you watch Canadian television, it’s almost inevitable that you’ll come across advertisements for over-the-counter (OTC) drugs – the ones that you can buy without a prescription.

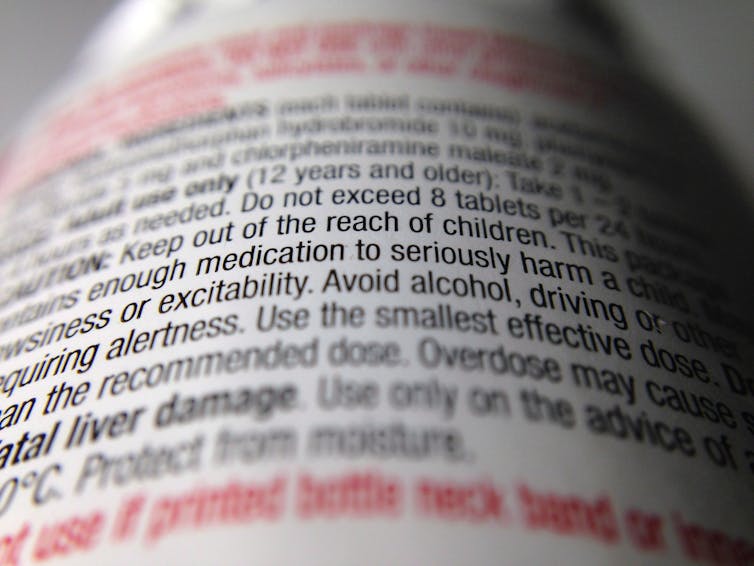

The ads are more than happy to tell you about the benefits – how your pain will be relieved, your skin cleared up, your allergic symptoms vanquished. Safety information in these ads, however, is virtually non-existent.

If you’re quick and have really good eyesight, you might catch a message in small print at the bottom of the ad that runs for two to three seconds. It says that to make sure that the drug is right for you, you should read the label. Missed that message? The other night I missed that message in three different ads.

One of the results is that in the emergency department in Toronto where I work, we see alcoholics who have further damaged their liver because they took too much acetaminophen.

We see people with psychotic symptoms because they took too many antihistamines.

There was no warning about these safety problems in the ads. Some of this information was in the label, but any message about reading the label was highly likely to have been missed.

Health Canada relinquished responsibility

It wasn’t always this way. Up until the end of February 1997, Health Canada was directly responsible for clearing the scripts for TV ads for OTC drugs. A 1993 review found that approximately one third of these scripts failed to comply with regulatory requirements.

At the start of March 1997, the responsibility for clearing consumer-directed broadcast advertising for OTC drugs was transferred to Advertising Standards Canada (ASC), a national industry association.

Crucially, the role of ASC was only to review the ads, not to regulate them.

Health Canada continued to set minimum standards, but at the same time also stopped adjudicating complaints about ads.

After this transfer of responsibility, there is no public record of any evaluation of the adequacy of the new system in complying with Health Canada’s regulations.

Agencies regulate themselves

Despite never having done an evaluation, in August 2006, Health Canada announced its intention to further loosen control over this type of advertising.

Under the new proposed system, Health Canada would no longer endorse specific agencies performing these pre-clearance activities. Rather, it would let agencies self-attest that they had the ability to meet these criteria.

In other words, agencies would regulate themselves and the public would have to rely on them being honest.

The equivalent would be for students to “self-attest” that they had not cheated on an exam and for teachers to trust them.

ASC itself pointed out the weaknesses in what Health Canada was proposing. It noted that the new system “could…result in the mistaken belief [that agencies possess the requisite knowledge, expertise and systems to perform this function]. This lack of understanding and expertise could lead to review errors that compromise consumer health and safety.”

Virtually unreadable messages

Another part of the move to change the oversight of OTC promotion was a 2006 invitational roundtable, sponsored by Health Canada, on the inclusion of risk information in advertising.

At the roundtable, a wide variety of opinions were expressed as to how much safety information should be included in ads. Some participants wanted more detailed information provided, some advocated for “black box” warnings for certain drugs, others felt that labels and inserts should be more user friendly.

Health Canada’s position was that there should be a verbal cautionary statement in TV ads, but it was willing to accept visual disclosures – provided they were “clear, visible and of a sufficient duration to be effectively read and understood by consumers.”

What we got was self-attestation with virtually unreadable messages.

People deserve to know about the safety risks of medicines that they buy. It’s time Health Canada took back the regulation of OTC advertising.![]()

Joel Lexchin is an associate professor of family and community medicine at the University of Toronto, professor emeritus of health policy and management at York University, and an emergency physician at the University Health Network.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article, including his disclosure statement.