U of T prof uses the ubiquitous banana to explore capitalism's history in the Americas

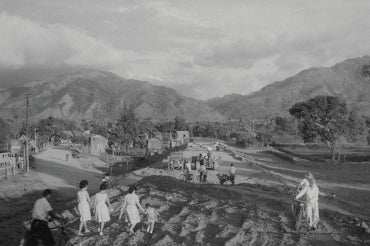

A scene from a banana town in Honduras run by the United Fruit Company (photo by Rafael Platero Paz)

Published: November 27, 2023

On the surface, bananas seem an uncontroversial fruit – delicious, nutritious and widely consumed all over the world.

But peel back the layers and you’ll find that the banana has much to teach us about capitalism, exploitation and political struggle, according to Kevin P. Coleman, an associate professor of historical studies at the University of Toronto Mississauga.

Coleman’s new research project demonstrates how the historical journey of this tropical fruit from Latin American farms to North American homes has been anything but straightforward.

“This is a story of the power dynamics these farmers experienced as a result of a foreign company working in their country, of the power dynamics in their societies and also of how they organized and succeeded,” says Coleman, whose project was supported by an Insight Grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council.

In Visualizing the Americas, Coleman documents the economic, social and political dynamics of the banana industry in countries such as Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Guatemala, Honduras and Panama. Working in collaboration with the UTM Library, he has created a comprehensive resource that reveals how worker exploitation, racial discrimination and ecological destruction have shaped the production and consumption of this popular commodity.

The resource can be used to inform current and future political struggles in Latin America and the Caribbean since it shows how poor and marginalized banana workers resisted unfair treatment by foreign employers.

“Visualizing the Americas is about insight, motivation, empowerment,” Coleman says.

Through historical records, photographs and interviews with scholars, Visualizing the Americas details the practices of the United Fruit Company, a multinational corporation based in Boston, Mass., that owned extensive land and employed tens of thousands of people in the Eastern Caribbean and Central and South America. The company created a workforce with a racial hierarchy that placed white Americans in upper-level positions and members of the local population – Black residents, mestizo and other mixed-race groups, Indigenous Peoples, Garifuna communities and immigrants – in low-wage, unskilled jobs. For the middle roles, including overseers, managers, timekeepers and engineers, the company recruited West Indian migrant workers from the British Caribbean.

To explain the ramifications of this racially stratified labour force, Coleman interviews Michigan State University history professor and author Glenn Chambers, who notes that the West Indian workers served as a “buffer” between management and manual labourers.

“West Indians were of African descent, but saw themselves as British, Christian, and ‘civilized’” and “viewed non-West Indians as outsiders and their culture inferior,” said Chambers, which “made organizing around Blackness difficult.”

The site also explains how the United Fruit Company exerted its influence on governments in the region to suppress the rights of workers. A key example was the Oct. 6, 1928 strike by Colombia’s banana labourers over long hours and low pay. Records show how the company was complicit in the military’s violent quashing of the strike, which resulted in the deaths of more than 1,000 workers. The Visualizing the Americas website features an archive of nearly 2,000 pages of letters, photos and other documents generated by the company from 1912-1982 that reflect unjust employment practices.

Visualizing the Americas also explores how exploitative labour practices make bananas so cheap, the environmental impacts of monoculture cultivation practices and the gains made by worker unions to create better working conditions in banana-growing regions.

There is a rich visual history of the life, culture and struggles of members of a banana company town in Honduras as captured by photographer Rafael Platero Paz, who sought to document the community’s social transformations over 57 years.

“I think it’s easy for many of us to forget that history is made by people,” Coleman says. “Many may not realize what an important role ordinary banana plantation workers played in the history of their countries.”