U of T researchers' drone-delivered AEDs offer novel approach to saving lives at home

Published: November 14, 2016

When a person goes into cardiac arrest, every passing minute hurts their chances of survival. Now, a group of University of Toronto researchers want to use drones to deliver life-saving automatic external defibrillators (AEDs) rapidly and directly to homes.

Justin Boutilier, a PhD candidate in the Faculty of Applied Science & Engineering, envisions a future in which a bystander or family member who witnesses a cardiac arrest can call 911, and within minutes, an AED is flown to their doorstep or balcony to be administered – before the paramedics arrive.

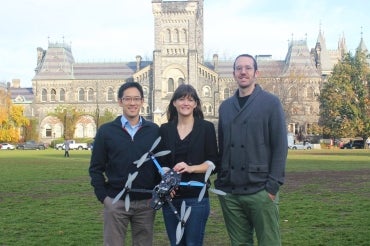

Boutilier is working under Associate Professor Timothy Chan, director of U of T's Centre for Healthcare Engineering, in collaboration with Assistant Professor Angela Schoellig and researchers from St. Michael’s Hospital's Rescu program, in order to turn the futuristic idea into a life-saving reality.

This project comes on the heels of research by Chan’s lab on cardiac arrests that occur outside of hospitals, and the lack of accessible AEDs in public locations during non-business hours. Boutilier is now focusing on reducing deaths from cardiac arrests that occur at home.

About 85 per cent of out-of-hospital cardiac arrests in Southern Ontario take place within a private residence.

“For those arrests, the public AEDs are not useful because it’s hard to get to them in time. It’s also not cost effective to put AEDs everywhere in the suburbs,” explained Boutilier.

Therefore, the survival rates are not good.

“Not only is the survival rate of private-location cardiac arrests low, the response times are also slower than public locations,” said Chan. “So we thought, we need to come up with something completely new.”

Chan and Dr. Steve Brooks, an emergency physician at Kingston General Hospital and frequent collaborator at Rescu, found a video of a prototype AED drone designed at Delft University in the Netherlands. A PhD student had developed the prototype, complete with a camera and microphone, which weighed only four kilograms and travelled 100 kilometres per hour.

“To us, the idea of using a drone to deliver an AED to private location cardiac arrests seemed like a no-brainer,” said Chan.

Of the many benefits to AED drone delivery: “You don’t have to worry about traffic. You could get the AED there faster than paramedics so the bystander can start treatment as early as possible. And that’s very important. Every minute that goes by, the chance of survival decreases,” said Chan.

To determine where drones should be stationed and how many are needed to serve a given population, Boutilier obtained historical cardiac arrest data from eight regions in Southern Ontario, including dense urban cities and sparse rural communities.

“We conducted our analysis by imagining that this technology was implemented five years ago and asking, what would the next five years have looked like?” Boutilier explained.

What they found was that they were able to shave several minutes off the median ambulance response times in both rural and urban regions, and drones could arrive ahead of ambulances more than 90 per cent of the time.

“The one challenging thing is that it’s hard to know the number of lives we could have saved, which is what we’re looking at now,” said Boutilier.

Regulatory restrictions present another challenge to implementation – aviation, including drone flights, is strictly regulated by Transport Canada. Current rules stipulate that users are prohibited from flying drones out of their line of sight.

Schoellig, the associate director of the Centre for Aerial Robotics Research and Education (CARRE) at U of T, believes these restrictive regulations won’t last for long. “It is a matter of proving safety and reliability of this new technology to the regulators. This will require more technological breakthroughs – for example, giving drones the ability to detect obstacles.

But drone technology has developed very quickly in the last five to 10 years,” she explained.

“Google and Amazon are already working on implementing delivery drones and have been lobbying the government to ease these regulations,” added Boutilier. “So if the government allows the drone delivery of commercial products, they would allow the delivery of AEDs, which is a life-saving matter.”

This past weekend, Boutilier and Chan presented their research at the American Heart Association Resuscitation Science Symposium in New Orleans, where Boutilier says he was excited to see the reactions from attendees.

“Depending on whom you talk to, the response can be very different. When I talk to medical professionals, some say, ‘That’s too futuristic,’ but when I talk to tech people their reaction is often, ‘This technology has been around for the last few years. We could do this tomorrow.’

“We’re trying to shake things up a bit within the field of health care, and change the way people are thinking about how we solve problems.”

In the near future, Boutilier hopes to pilot the project in Muskoka, a region that has a high rate of bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), and the slowest ambulance response time of all the regions they’ve gathered data from.

“I think the technology is there. I think the challenge is in the details of how to make this work,” said Chan. “It’s working through government regulations, coordinating with Emergency Medical Services, and making sure the public is behind this, that they have awareness of drones and its various purposes.

“But ultimately, it’s an idea that I think can really make a huge leap forward in our ability to get defibrillators to patients. I think within five to 10 years, drone deliveries will be a reality.”