Unearthing an ugly past: Forensic experts on the challenge of searching former residential school sites

Published: July 22, 2021

For Kona Williams, the discovery of hundreds of unmarked graves at former residential schools in B.C. and Saskatchewan – many belonging to children – has brought on a flurry of emotions: sadness, grief and anger.

Kona Williams

Kona WilliamsAs Canada’s first Indigenous forensic pathologist, Williams sees the ongoing investigations as the beginning of a long and complex process of identifying victims and reckoning with Canada’s brutal past. As the daughter of Cree and Mohawk parents, including a father who attended residential school, she is also steeling herself for the possibility that the searches may turn up members of her own family.

“We’re talking about children,” says Williams, who completed a fellowship at the University of Toronto’s department of laboratory medicine and pathobiology in the Temerty Faculty of Medicine.

“Dealing with the deaths of children is never easy – and I deal with death every day.”

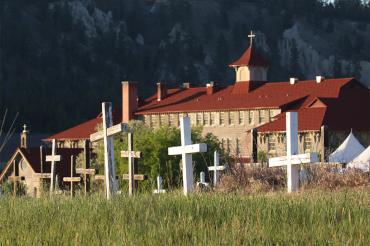

The discovery of unmarked graves near former residential schools, including one near Kamloops, B.C. in May, shocked many Canadians, although First Nations communities have long been aware of the abuse inflicted at the institutions, which operated from the 1880s to 1990s.

“We’ve known about this, but I think it’s hitting the whole country in a way it’s never quite hit before,” Williams says. “The gravity and the immensity of this is coming to the forefront.”

Williams’ father Gordon, a member of Peguis First Nation in Manitoba, was forced to attend Birtle Indian Residential School, northwest of Brandon.

“Growing up, he said very little about it, until I started asking questions,” she says.

Williams remembers asking her father for help with homework one day after school, only for him to say he didn’t learn the same subjects when he was younger. Instead, he cleaned barns, stables and did other farm work.

Instead of learning about the residential school system in public school or university, Williams says she learned about it through the Aboriginal Healing Foundation and Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada.

“Listening to survivors speak gave me the education I never had in school,” says Williams.

In recent weeks, Birtle school survivors have called for the demolition of the former residential school, while Birdtail Sioux Chief Lindsay Bunn has called for a search for unmarked graves similar to the one that took place in Kamloops.

Williams came to U of T in 2014 to conduct post-doctoral work in forensic pathology after completing medical school at the University of Ottawa. At the time, Michael Pollanen, a professor in the department of laboratory medicine and pathobiology in the Temerty Faculty of Medicine who is the director of the forensic pathology program, predicted Williams would become an “important liaison” between First Nations communities and the forensic medical community.

This week, Pollanen – who is Ontario’s chief forensic pathologist – told U of T News that Williams has “developed personal insights and scientific knowledge that would benefit the investigations of former residential schools.”

While open to the idea of contributing to the investigations, Williams says her current focus is sharing information about how forensics can help First Nations communities uncover the truth. She says that, depending on a community’s wishes, a fuller investigation may require a range of experts including: archeologists; forensic anthropologists, who look for signs of cause of death in bones; and genealogists, who can use DNA samples to match the deceased to living kin.

Experts warn that investigators will face many challenges.

To take one example: The ground-penetrating radar technology used in some preliminary investigations can detect disturbances in the soil but can’t “specifically detect the presence of skeletal remains,” says Tracy Rogers, an associate professor in the department of anthropology at U of T Mississauga and director of its forensic science program.

She adds that attempts to identify the children found in unmarked graves would require DNA samples from living relatives and exhuming all the individuals at a given site.

“It is not possible to excavate and examine only some of the children in a cemetery or burial ground because most of the records are incomplete, and it is not possible to determine who is in which section of the cemetery,” she says.

“Most communities contemplating trying to identify the children from residential school burials will face the decision of working to identify all of the children, or none of the children.”

Detailed analysis of skeletons can reveal the specific nature or frequency of injuries that took place, adds Rogers. But she notes it’s often insufficient to determine cause of death.

Williams says she is frustrated when the evidence can’t provide all the answers that relatives seek.

“Every time I have to say the cause of death is undetermined it’s very disappointing – and I can't imagine what it would be like for families,” she says.

Williams recommends establishing a national committee that combines forensic experts, Elders and residential school survivors to consult with Indigenous communities as they contemplate moving forward with investigations.

She says the recent discoveries of unmarked graves appear to mark a turning point.

“I really wish my dad was still here so I could talk to him and tell him about this, because I think he would be relieved that this is finally happening,” she says.

“After 150 years of this, finally these children are going to be, hopefully, honoured as opposed to just forgotten. I don't think we've forgotten, but the fact that the response from the vast majority of Canadians has been so overwhelming – I think now it's becoming real.”

Residential school survivors or those impacted by residential schools can access support through the Indian Residential Schools Crisis Line at 1-866-925-4419. It is available 24 hours a day for anyone experiencing pain or distress as a result of their residential school experience.

Resources available to the U of T community:

U of T students can access supports through the university’s Indigenous Student Services while U of T My Student Support Program (SSP) offers students 24-hour confidential support that can be accessed over the phone in 35 languages, while support scheduled in advance is available in 146 languages.

Staff, faculty and librarians can access the Employee and Family Assistance Program which offers confidential short-term counselling and support for issues relating to mental health, health management and workplace well-being. To access EFAP services, please contact Homewood Health at 1-800-663-1142.

U of T’s Office of Indigenous Initiatives is available to connect Indigenous students, staff, faculty, librarians, and community members across U of T. For staff, faculty and librarians, there are also classes on reconciliation available through the Centre for Learning, Leadership & Culture. Students, meanwhile, can explore Indigenous-focused learning opportunities through the Career and Co-Curricular Learning Network.

Beyond U of T, the following resources are also available to members of the Indigenous community:

- Toronto Aboriginal Support Services Council (TASSC)

- 2 Spirited People of the 1st Nations

- Anduhyaun Inc.

- Native Child & Family Services of Toronto

- Native Women’s Resource Centre of Toronto

- Toronto Council Fire Native Cultural Centre

- Dodem Kanonhsa’

- Native Canadian Centre Toronto

- Ontario Federation of Indigenous Friendship Centres

- Na-Me-Res (Native Men’s Residences)

- Anishinawbe Health Toronto